Having recently covered land navigation; wherein we learned how to determine where we are, where we want to go and how to get there; this article explores the “how” a bit more closely. If our movement from point A to point B must be accomplished without being detected by potential adversaries, then we must also incorporate individual stealth movement techniques.

The modifier of “individual” in “individual stealth movement” only denotes that the techniques are performed at the individual level, that is by each person. Whether operating alone, as an isolated individual, or as just one member of a larger group, individual stealth movement techniques are equally important in avoiding detection.

For our basic framework, we rely on methods taught in the military of the US and other nations; including those of dismounted infantry, and in fact all soldiers generally, but also skills taught to more specialized troops, particularly snipers and reconnaissance personnel, but also drawing squatting movement techniques from Russian martial arts. We have, however, further expounded upon these techniques with insights from naturalists, survivalists, trackers, hunters, Appalachian and Native American/First Nations people lore and our traditional Japanese martial arts training.

Although numerous variations and other techniques exist, especially for walking, the basic methods we use in each mode of travel are listed below. Future posts may go into greater detail with regard to each of these methods, as well as introducing variations and supplementary techniques.

Walking

-Fox walk

-Crouched stalking walk

Squatting Movement[1]

-Squatting walk

-Long-leg creep

Crawling

-Crawling on hands and knees

-High crawl

-Low crawl

-Sniper crawl

Running

-Silent running

-3-5 second rush between positions of concealment

Each of these stealth movement techniques is intended to deny “target indicators” to potential threats. The indicators we are primarily concerned with reducing here are either visual or audial and direct in nature. Mitigating indirect indicators, such as one’s footprints or tracks and the disturbed vegetation one leaves behind, are discussed separately under counter-tracking measures.

After the main senses of sight and hearing, the sense of smell is the next most important in avoiding direct detection. Olfactory indicators can be mitigated through means other than movement techniques, such as by positioning oneself upwind of potential adversaries, careful dietary and hygiene choices, masking one’s smell, and avoiding alcohol and tobacco products.

The senses of taste and touch are of less practical relevance here, as they are not as likely to lead to detection in any but the most close-range of encounters, that is if taste factors in at all, other than through its relation to the sense of smell. Thus here we are primarily concerned with reducing direct visual and audial target indicators.

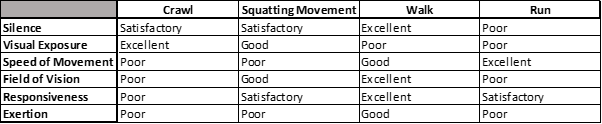

But beyond the degree of visual exposure or the level of noise inherent in each mode of travel, there are also several other considerations to be taken into account when selecting the most appropriate mode of travel for a given situation. These include what each mode of travel affords in terms of the speed, maintaining one’s field of vision and thus situational awareness, ability to respond quickly to changing circumstances and the degree of physical exertion required to perform each technique.

As depicted in the table below, we have assigned a grade to all four modes of travel in each of these six categories (1. silence and 2. visual exposure, as the main concerns with regard to stealth; but also the considerations of 3. speed, 4. field of vision, 5. responsiveness and 6. physical exertion). From least to most desirable or beneficial, the grades assigned are: poor, satisfactory, good and excellent. This table serves as the basis of discussion for the following paragraphs. We will not go into detail on each individual movement technique, but will instead concentrate on the overarching modes of travel. Later articles, however, may undertake such a detailed endeavor for individual techniques and/or modes of travel.

Walking

In most situations, walking techniques are preferred due to their superior silence, field of vision, ability to respond quickly to changing circumstances and comparative ease in terms of physical exertion and thus energy preservation, not to mention their generally faster speed of movement, the latter of which is only surpassed by running methods. The main drawback, however, is a higher profile that increases the risk of visual detection when there is insufficient concealment.

When available concealment; whether provided by vegetation, terrain features or man-made structures; is too low in height to conceal one’s entire standing form; whether fully upright in the fox walk or crouched in the stalking step; one must resort to crawling or squatting movement to avoid visual detection. Yet both means of travel can be significantly more physically demanding than walking methods, in addition to other limitations in terms of field of vision and responsiveness. Hence, these should only be used as long as necessary, returning to walking as soon as there is sufficient concealment available to hide one’s standing form.

When concealment is sporadic and/or there is a pressing need to move more quickly than what walking already affords, then one must resort to one of the running methods. Yet again, because of the increased physical exertion as well as the reduced field of vision and ability to react, but also because of the greater amount of noise produced by running, as soon as there is sufficient concealment to hide one’s body while standing and/or there is no longer a need to move more quickly, then one should return to the default of walking.

If the situation demands a lower profile, darting between sporadic positions of concealment and/or faster movement than what walking methods provide, one must guard against laziness and do what must be done to avoid detection, but only as long as is truly necessary.

Crawling

In terms of reducing one’s visual exposure, crawling offers the best option out of all the movement techniques. That said, in addition to the reduced speed and increased degree of exertion required, one’s field of vision as well as one’s ability to respond quickly to changing circumstances are both substantially hindered.

Squatting Movements

While not much better in terms of speed and significantly worse with regard to exertion, methods of squatting movement do have advantages over crawling, in that they provide better responsiveness or mobility, and even more so, in terms of a better field of vision. Because of the physical exertion involved, it is recommended that squatting movements are only used to travel very short distances, such as moving past a window (beneath it) to avoid silhouetting oneself. Since it is easier to move into and out of a squatting position than one of lying prone on the ground, they can be used to travel short distances of increased visual exposure. For distances greater than two or three meters, however, crawling is preferred to preserve energy.

Running

The primary benefit of running is the increased speed of travel that it affords. Such speed may be employed to evade an immediate threat, reach a nearby safe haven or to accept a certain amount of risk with regard to a greater degree of visual and audial exposure while also limiting the duration of such exposure, that is darting between positions of concealment in the hopes of not being seen or heard. In all three cases, there may sometimes not be much in the way of options to do otherwise.

If for whatever reason, an increased speed of travel is imperative, then running for an extended period may become necessary. Yet this should of course be seriously weighed against the costs in terms of physical exertion and the risks of exposure, disorientation, dehydration and/or injury, but also the likelihood of expected payoffs, such as discovery and rescue, or reaching a safe haven, such as a public area, hospital or police station. Thus, depending on the situation, one may choose running as their default mode of travel. Factors like terrain, weather conditions, distance to a safe haven, one’s level of physical fitness or that of one’s companions, clothing (especially footwear) and likewise, the mobility of potential threats should be considered while making such a decision.

In contrast to running for an extended period, in the case of a sparsity of concealment, one may well need to temporarily resort to scurrying short distances, darting like a mouse between the limited opportunities that do exist.

Yet the benefit of speed can also become a weakness, and it naturally comes at the cost, however brief, of producing an increased level of noise, alongside a heightened profile, reduced field of vision and decreased responsiveness, due to focusing on one’s path of travel and next position, not to mention the greater degree of physical exertion entailed.

Pertaining to the level of sound produced, if running across clear, open and moist terrain, one can travel remarkably silently, but if breaking brush and/or trampling dry or conversely saturated ground, the level of sound produced will be greatly increased. Additionally, one’s visual profile, since standing, is basically the same as if walking, though reduced in terms of the duration of exposure.

It should be noted, however, that movement attracts attention, and fast movement even more so. Hence this truly is a gamble, though one in which the odds can be stacked, such as by moving only when the sound of one’s movements will be masked by other sounds; like wind, traffic or flowing water; or when potential observers are likely to be distracted by other occurrences and focusing their attention elsewhere.

Although the main benefit of running methods is their speed, it is because of the speed at which one is travelling and the resulting momentum, combined with a focus on arriving at one’s next position of concealment, that there is both a reduced field of vision and a lessened ability to respond to emerging threats or obstacles. The faster one moves, the more rapidly one’s environment changes. This leads not only to an increased danger of disorientation and becoming lost, but also more immediately of encountering unforeseen obstacles and injuring oneself, particularly in low-light conditions and/or dense vegetation.

In the same vein, with regard to dealing with assailants wishing to obstruct one’s movement, such as through tackling to apprehend, a potentially fruitful avenue of inquiry might be to explore the methods used in American football to elude the opposing team’s defenses.

General Guidelines for Individual Stealth Movement

There are certain guidelines that apply to two or more of the above categories. These are as follows:

-Only use crawling, squatting movement, running techniques or the stalking step if the situation demands it. Your movement technique should be appropriate to the circumstances to avoid enemy observation or audial detection.

-Keep in mind that one’s movements will likely not be heard further than 300 to 600 meters away, and thus visual detection is the primary concern unless the threat is believed to be within or closer than that range.

-Use available cover and concealment, moving within the dead space provided by the terrain, vegetation or manmade structures.

-All forms of movement create sound, some more than others, but as a general rule, the faster one moves, the louder one’s movements will be. Be patient and take your time if necessary, that is when the enemy is known or believed to be in close range and contact is likely. One stalking step may take a full 60 seconds or more to ensure complete silence.[2]

-The inevitable sound produced by one’s movements, however slight, can be mitigated by masking it with sounds like the wind or city traffic. This is especially important for running.

-Stop periodically to look, listen and smell, familiarizing oneself with the baseline of one’s environment so as to be able to recognize when something has changed and there is a potential threat.

-Deer walking is a method described by ReWildUniversity co-founder and head instructor, Kenton Whitman.[3] It makes frequent use of SLLS to produce a stealthy effect that is similar to how deer walk in the forest.

-If you have inadvertently made a noise and believe you may have exposed yourself, freeze and listen/observe/smell your surroundings to assess whether or not you have been compromised. If not, continue as before; but if so, then you may need to revert to a running method to remove yourself from immediate danger.

-Maintain situational awareness by remaining undistracted and alert audially, olfactorily and visually, scanning ahead of oneself as well as to the sides and occasionally rearwards.

-Employ wide-angle vision, the opposite of tunnel vision, to take in the fuller view of one’s surroundings that peripheral vision adds.

-Use the hands and/or feet to probe, test and/or clear the path ahead of oneself. This is particularly necessary in low-light conditions, but it is also needed at other times so that one does not stare down at one’s feet or hands while making the next step or hand/arm placement and thus lose situational awareness. Let your hands and feet supplement your eyes.

-With all techniques except those for running, carefully transfer your weight after having already tested the ground on which you are about to step or otherwise move.

-Lower your center of gravity to maintain balance and reduce visibility, getting as close/low to the ground as each mode of travel comfortably allows.

-Stay calm, relax and move with fluidity. An upset mind and a rigid body are less able to adapt to changing circumstances and more likely to produce unwanted noise, not to mention the wasted energy (emotional and physical) from such increased tension.

-Breathe continuously, as holding one’s breath could lead to a tell-tale gasp in the event of an unexpected occurrence, like stepping on and snapping a twig or encountering an adversary. Breathing also helps in remaining calm.

Practicing Individual Stealth Movement

With regard to practicing these techniques, while crawling and running methods are easily learned and performed, although a degree of physical conditioning is required, squatting movements and walking techniques are more nuanced and need to be practiced more in order to be employed effectively. Squatting movements require not only conditioning, but also a certain measure of flexibility, balance, poise, agility and fluidity of movement, which do not come easily without practice. Moreover, this ability atrophies if not maintained. Walking methods in particular should be practiced in a variety of settings and on different types of surfaces, but especially in areas one frequents often, such as one’s home, place of work and the routes used in between such locations.

In addition to practicing on one’s own, there are multiple ways of working with training partners to test for stealth. One example is a game played by boy scouts, wherein one sits blindfolded on a log, guarding an object that represents a “pirate’s treasure,” while others attempt to stealthily walk toward him and take it. As soon as he hears someone, he points to them and they are “out.”

Even more challenging than human training partners is the animals we encounter in the wilderness. If we are able to approach birds, deer and other fauna without alerting them to our presence, or at least without startling or making them feel threatened, then have accomplished much.

But this leads us to a very important point. When practicing these techniques on public land, we have an ethical obligation to avoid frightening and thus causing emotional distress to others. Thus, we recommend that in the event one is spotted, as soon as this is realized, to smile and extend a friendly greeting like a hearty “Hello” or a hand wave to the person or persons and then continue with your activity. This should not only help to allay their fears, but it will also reduce the likelihood that you will have to explain yourself to the police.

Movement in Special Situations

It is also important to train for movement in a variety of special situations; such as through narrow spaces, while carrying a pack or negotiating slippery or steep terrain (moving both uphill and downhill). Such special situations can also have a direct impact on stealth, which is why they are mentioned here. For instance, if due to improper movement technique, one slips and falls, this increases not only one’s vulnerability, but also their likelihood of being discovered. The main special movement situations we address are as follows:

-Narrow spaces

-Ruck marching

-Walking/running on slippery surfaces such as ice

-Steep terrain

[1] These two squatting movements were adopted and adapted from Appendix II of Scott Sonnon’s Body Flow: Freedom from Fear-Reactivity (Atlanta, GA: RMAX.tv Productions, 2003), 3-4, 11-12. For Sonnon’s diverse array of initiatives, visit RMAXInternational.com.

[2] For an excellent video on stealth walking, see Sigma 3 Survival School, “Art of Stalking Tom Brown III,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hjnhnmBU_rU (accessed October 3, 2020).

[3] ReWildUniversity, “Deer Walking — an easy method to develop more ‘woods stealth’,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ImPgGJ0d0fA (accessed October 2, 2020).