It seems particularly appropriate that this article follows not only the introductory articles on the fundamentals of stealth for self-protection, since these are prerequisites for urban stealth, but that it also follows immediately after the article Terrain Analysis for Escape and Evasion. In that article, we made reference to the categorization of stealth skills attributed to the feudal Japanese ninja known as the tenchijin santon no hō (天地人三遁の法, “heaven, earth, man-three methods of escaping”) and more specifically to its subset known as the chiton jūppō (地遁十法, “10 earth methods of escaping). Among these, the discipline of doton (土遁, “earth escape”) is closely related to that of okuton (屋遁, “house escape,” “abode escape,” “roof escape” or “building escape”).

When approaching this topic, it must first be emphasized that stealth for escape and evasion in the context of civilian self-protection should only be attempted when necessary to temporarily avoid interdiction by hostile elements until a safe place or source of assistance can be reached. If in a public area with bystanders around, it would usually be far wiser to attract attention rather than to avoid it. Bystanders could become sources of aid or at the very least, their presence could deter assailants who wish to avoid having witnesses to their intended crime.

Similarly, if a safe place like a populated public area, police station or hospital is nearby, priority should be placed on reaching this place as quickly as possible and getting help immediately. Thus it is imperative to have already identified potential safe places in the vicinity of where you live and work, or are staying and visiting while travelling, as well as areas that you frequent. One should also identify and rehearse travelling along primary and alternate routes to such locations. Such advance preparation must also include knowing the location, routes to and closing and opening times of late-night establishments in the area like restaurants, bars or gas stations.

There may be situations in which safe places or sources of potential aid cannot be reached directly or are not immediately available, like during the nighttime after most have gone home and are asleep or at least indoors. It would be best to avoid being caught in such situations to begin with, but in the event one is and is faced with a potential threat, it may be advisable to employ urban stealth movement to facilitate reaching a safe place or source of aid.

Previous articles addressing individual and group stealth movement provide a foundation which can be applied and adapted to a range of environments. These basics are initially best practiced in natural wilderness settings to reduce the variables and problems that arise when man-made structures and settings are introduced into the equation. Urban environments offer multiple unique challenges as well as opportunities.

The same basic principles and techniques of individual and group stealth movement used in natural settings apply, but with additional considerations. In urban settings, threats may present themselves more immediately, at much closer ranges and from any direction, including from above and below. Thus, further methods must be employed in order to detect and avoid threats in an urban setting.

In two future articles, urban stealth movement methods are divided into those employed outdoors and those used in indoor situations, though there are some guidelines, principles and considerations that apply to both situations. These are the topic of the present article.

General Guidelines for Urban Stealth Movement

The following points should be taken as basic general guidelines for urban stealth:

-Maintain a high degree of situational awareness, since the threat can appear suddenly and at particularly close ranges as well as from any direction, including from above or below.

-Remain cognizant of “dead space” as well as shadows, and when not occupying and using such areas for one’s own concealment and camouflage, give them a wide berth, such as by “cutting the pie” around corners, furniture or bushes.

-Avoid silhouetting, such as when moving past windows and doorways or negotiating obstacles.

-Visually reconnoiter for threats and hazards as well as one’s next position before passing corners, crossing obstacles, traversing open areas or initiating any other movement.

-Identify your next location of camouflage, concealment and cover (CCC) before proceeding to the next.

-Move rapidly between positions of CCC.

-Avoid being exposed in open areas (like courtyards, parks, gardens, squares, streets, alleyways, etc.).

-Make use of dead space and stay in the shadows as well as close to structures or significant vegetation.[1]

The Importance of Sound in Urban Settings

In addition to these general guidelines, we should reiterate how encounters and distance from hostile personnel in urban settings can be at very close ranges when compared with natural settings, thus also elevating the importance of sound. Moreover, echoes off of surfaces can exacerbate any noises produced. Further still, in natural settings like forests, vegetation can hinder the movement of sound waves, thus reducing the chances of being detected audially, whereas open areas in urban spaces present no such barrier, allowing the sound waves produced by one’s movements to travel unobstructed.

Yet the situation is not always so bleak, since in densely populated areas, there may be significant background noise, such as from traffic, and in some places this is true at all hours of the day. These can be used to mask the sounds of one’s own movement, though adversaries may also take advantage of this to mask their own movement.

As a result of such factors as described above, sound is often of greater concern in urban settings than in natural ones. Accordingly, it is important to consider how to reduce and/or mask (through ambient noise) the sounds produced by one’s own activities, such as opening or closing doors as well as simply walking across a surface.

Pertaining to the latter, it is important to be cognizant of the surfaces one is traversing as well as the type of footwear one has on. Gravel and creaking floors are extremely difficult to cross without making compromising noises. In fact, gravel is commonly used outside of residences to deter burglars, just as the so-called “nightingale floors” were used in medieval Japanese castles to make intruders easier to detect. In contrast, grassy earth, such as found on a lawn or in a park, along with clean, hard surfaces like concrete, asphalt or marble, tend to be much easier to cross silently.

Yet this of course also depends on one’s footwear. Dress shoes or high heels produce loud and distinctive sounds while, true to their etymology, sneakers are much more conducive to silent movement, as is going barefoot.

Hence, whenever selecting routes for stealth escape and evasion in urban settings, the nature of the surfaces to be crossed as well as one’s own type of footwear must be factored in. In this same vein, it is important to practice stealth in and around areas that one frequents often, like one’s home and workplace, to ensure an awareness of problem areas as well as places that can be traversed in relative silence to facilitate rapid route selection should the need arise.

Principles of Operating in Urban Terrain

The abovementioned general guidelines for urban stealth movement are relatively sound and applicable in the vast majority of situations when practicing stealth for escape and evasion in urban settings. But there are also a handful of principles for Military Operations in Urban Terrain (MOUT) that may also be helpful here. These include Surprise, Security, Simplicity, Speed and Violence of Action (S4V).

Yet military operations and civilian escape and evasion for self-protection are two very different things. So it must be considered whether or not; and if so, to what extent; these also apply for civilian escape and evasion purposes (or even whether or not they apply to all military operations in all circumstances). We do so with each of these five MOUT principles here, but particularly with the principles of speed and violence of action:

Surprise-In the original military context of this principle, it refers to conducting offensive operations against an enemy force at a time and/or place that they would not expect and not be prepared for. Yet if we reverse the direction of this principle and consider that potential assailants also seek the advantage of surprise, it can provide some valuable insights for situational awareness and preparedness generally.

Criminal and/or terrorist attacks against a specific target (rather than a target of opportunity) are most often conducted at the target’s residence or place of work, where they are not only most predictable (and thus targetable), but also where they may be lulled into a false sense of security due to the familiar and routine nature of these places and the activities they engage in there.

But whether in settings that are familiar or unfamiliar to the intended victim, assailant’s may well seek to exploit situations in which their prospective prey may be distracted to achieve surprise, and thus the upper hand. Some common examples include when their target is engrossed in their mobile phone, entering an ATM PIN or fumbling with their keys outside of their vehicle or a building door.

These insights, however, relate more to personal security practices in general rather than specifically to the topic of this article: urban stealth. So to reverse the direction again for our purposes here, certainly we do not want a pursuer to know or guess what we are doing or where we are going. Thus, we can conceal our intentions and even use deception to mislead (and eventually surprise) pursuers.

This can be achieved, for instance, by basic misdirection, moving in one direction while in view of the pursuer but changing direction once one has left their field of view. This has already been discussed in the introductory article, “Fundamentals of Stealth for Self-Protection I: Introduction and Three Approaches to Hiding,” and it is also an invaluable and fundamental anti-surveillance technique for “losing” a surveillant or other pursuer. This can be done, for example, by turning onto a street and then onto another street while concealed by a building, or also by entering a building and then leaving that building through another exit. Yet the topics of surveillance detection, anti-surveillance, counter-surveillance, etc., are vast and will be discussed in a future article.

Gaining the advantage of surprise is also closely related to two of the other principles of operating in urban terrain discussed below: speed and violence of action.

Security-Security is always important, but given how in urban environments threats can appear quite suddenly, at very close ranges and from any direction, including from above and below, maintaining vigilant security and situational awareness becomes especially crucial in urban settings.

Simplicity-Similarly, keeping plans simple is always a good rule of thumb for any setting, but it is especially true for urban environments, which can be highly complex in and of themselves. Thus, to avoid making the situation unnecessarily more complex and difficult to manage, echoing the sentiments of Occam’s Razor, it is best to keep plans as simple as possible. This reduces the number of variables that could go wrong, makes the plan easier to execute (which is especially important in situations of heightened stress), allows for flexibly adapting to rapidly changing circumstances and, if operating in a group, facilitates ease of communication and the understanding of plans. Such simplicity should also extend to the routes selected for use. Safe places and specific primary and alternate routes to get there should also be selected and rehearsed when staying in an unfamiliar area. Furthermore, although memorizing all of the streets in a new city is unrealistic, one should have a basic familiarity with the general layout and street plan.

Speed-Obviously, we want to choose the fastest and most direct route possible to reach a safe place. But speed is of course not the only factor, as such choices as route selection and the movement techniques used must also be made in light of, for instance, safety and security, particularly with regard to the considerations of observation and CCC.

Yet there are also variables like the enemy situation and whether one is being actively pursued or simply in a potentially dangerous situation, and if the adversary or potential adversary has knowledge of one’s location and/or intended destination and the route to be taken there.

The complexity of the question of whether speed is best in urban environments can be illuminated through an anecdote from personal experience. When the present author was a platoon leader carrying out various types of mounted patrols in a major city in the Middle East in 2005, there was a heated debate about whether it was best to move quickly (as the MOUT principles dictate) or to move slowly (in direct contradiction to these earlier-established MOUT principles).

The formerly doctrinally sound means of operating in urban terrain demanded speed, allowing speed to serve as one’s security by reducing exposure to enemy observation and targetability by enemy ambushes. Yet such speed also had drawbacks, which led to a change in doctrine for this particular theater of operation.

Foremost among these disadvantages include how such speed increases the risk of encounters leading to casualties among innocent civilians. This was a counterinsurgency (COIN) fight, in which the guerrillas moved “amongst the people as a fish swims in the sea,” to quote Mao Zedong’s “little red book.” It was not the meeting of two conventional military forces in an urban area, like the Battle of Stalingrad.

Another disadvantage was that increased speed decreases one’s ability to scan for threats. If blowing past the kill zone of a small arms fire ambush in a heavily armored vehicle, this may not be as problematic, but if the more common and more dangerous threat is improvised explosives devices (IEDs) that are victim-operated (booby traps), or command-operated by a competent operator, and have the ability to penetrate the armor of one’s vehicle, then it may be better to slow down and try to find such IEDs before setting them off or moving near them. This is especially true if such slowness also supports the overall COIN mission and helps to prevent civilian casualties.

This doctrinal shift by theoreticians was not readily accepted by all of those actually carrying out missions on the ground. Such tension between the old established doctrine of speed as security versus the new philosophy of slow and careful movement to prioritize detecting IED threats could be seen in flyers and pamphlets distributed to convoy personnel with headlines like “You Can’t Outrun the Blast.”

Yet even in earlier manuals, the issue was not so clear. A version of the Ranger Handbook dating from 2000, just before the “War on Terror” began, also exhibits some ambiguity and an impetus to balance speed and caution.

While it does first advise allowing speed to act as one’s security, it also seems to actually pay more attention to caution. It does so by recommending to “Move in a careful hurry,” pointing to the saying that “Slow is smooth, and smooth is fast,” as well as recommending to “Never move faster than you can accurately engage targets,” and of course, “Exercise tactical patience.”

Notwithstanding the vastly different types of activities and objectives, if modern professional militaries cannot decide whether or not it is better to move quickly or slowly through urban terrain, what is the average individual faced with danger in an urban environment to do? Can they choose any course of action with certainty or confidence?

The answer proposed here to the question of whether to move quickly or slowly in urban settings is that “it depends.” Every situation is different and it is best to use one’s own judgement for one’s particular situation as to whether it is better to move with speed or with slower cautious movement.

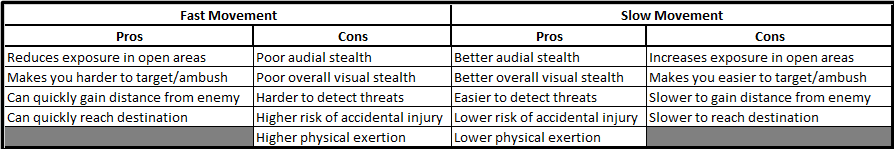

To help in this, we consider some of the advantages and disadvantages of fast as well as of slow movement below.

It is ultimately argued that, overall, it seems that slow movement is in fact probably the best default mode for civilian escape and evasion, changing to fast movement only in situations where it becomes more beneficial or necessary.

This advice (as well as the entire discussion below) is actually applicable for all situations, whether urban or rural. Yet we have treated this in depth here because, first, this thesis runs counter to the fourth of the S4V principles of MOUT, and second, urban environments may require more frequent alternation between slow and fast movement, thus a clear understanding of when to use which approach is especially important.

Fast Movement Advantages

-Reduces duration of exposure in open areas

-Makes it more difficult to be targeted or ambushed

-Rapidly creates distance between oneself and hostile elements

-Allows for reaching a safe place sooner

Fast Movement Disadvantages

-Produces more noise, higher risk of being compromised audially

-The eye detects rapid movement easily, and is in fact drawn to it, higher risk of being compromised visually

-More difficult to detect threats before encountering them

-Higher risk of accidents and injury

-Higher physical exertion

Slow Movement Advantages

-Produces less noise, lower risk of being compromised audially

-The eye does not detect slow and steady movement as easily as rapid and erratic movement, lower risk of being compromised visually

-Can more easily detect threats to oneself before encountering them

-Lower risk of accidents and injury

-Lower physical exertion

Slow Movement Disadvantages

-Increases duration of exposure in open areas

-It is easier for the enemy to target you

-Is slow to create distance between oneself and hostile elements

-Takes longer to reach a safe place or other objective location

To summarize the above lists of pros and cons, rapid movement makes it harder for the enemy to ambush you as well as quickly increases the speed at which you can gain distance between yourself and an adversary along with increasing the speed in which you can reach a safe place or other objective. These benefits come at the cost of reducing stealth (with the exception of quickly traversing open areas to risk exposure), reducing the ability to identify threats before encountering them, a higher risk of accidents and injury as well as a higher degree of physical exertion.

Conversely, slow movement favors stealth (with the exception of crossing open areas) as well as the ability to identify threats before encountering them. It also lessens the risk of accidents and injury and requires a lesser amount of physical exertion Yet the drawbacks to slow movement are that it makes it easier to be targeted by an ambush and slower to distance oneself from an adversary or reach a safe place or other objective. These pros and cons are also summarized in the following table:

Having laid out the advantages and disadvantages of fast versus slow movement in urban settings, we now seek to determine when each approach would be appropriate. The following are probably the most relevant questions to ask in this regard.

1-Does the enemy see you or know where you are?

If so, then CCC is no longer an immediate priority and, while one should remain alert to the possibility of any other threats that may emerge, for the time being, avoiding and escaping the threat that has been identified should be the focus. Thus, speed is probably the better choice here, whether fleeing directly to a safe place or to “lose them” and find good CCC until one can reach a safe place.

If they do not know your location or you are unsure, then it may be better to err on the side of caution, using slow movement and stealth to prevent them from finding you and beginning pursuit.

2-Do you know where the enemy is?

If so, then you must use your judgement; based on such variables as distance, available CCC, weather conditions, etc.; as to whether you can move quickly without compromising your position. Though since you know where the enemy is, you may be able to assume some risk and move more quickly while traversing areas where you know you will not run into them, walk into their ambush or expose yourself to them.

If you do not know where the enemy is, however, then it may be better to move more slowly and cautiously, thus increasing your chances of spotting them before they spot you.

3-If you move as quickly as you reasonably can, are you likely to reach a safe place before the enemy can intercept or otherwise attack you?

If yes, then speed is likely preferred, but if not, then it may be better to exercise caution and move slowly to avoid being detected. If the enemy already knows your location, as already discussed above, it may be better to move speedily to lose them and reach the nearest CCC and then to move more slowly until you reach your objective.

4-Are there any medical emergencies, particularly those that involve threats to life, limb or eyesight, that require immediate attention?

If so, then speed is clearly of substantial importance, though this has to be balanced against the risk of taking on further casualties.

5-Are there other compelling reasons why there is a time sensitive need to reach a safe place or other objective?

Examples of such other compelling reasons include the risk of exposure in extreme weather conditions, when sunset is disadvantageous, when sunrise is disadvantageous or the approaching closing times of an intended safe haven like a shopping center. These also clearly make speed desirable, but only if it can be achieved without incurring worse consequences.

6-Are you in a familiar area?

Familiarity with the area you are operating in may allow you to move with greater certainty and thus also speed. It may also help you to more easily identify anomalous deviations from the baseline norm of a given area, deviations which may indicate a potential threat. If you are in an unfamiliar area, however, it may be better to move more cautiously, and thus slowly.

7-How far away are you from your destination?

Greater distances require you to pace yourself, moving slowly and taking frequent breaks. Also remember, unless there is immediate danger at your current location, do not move until you have some plan for where you are going and why.

8-Is maintaining stealth feasible?

That is to say, is sufficient CCC available to remain visually undetected and does the environment and distance from one’s adversary allow for a reasonable expectation of remaining audially undetected? If it is unreasonable to think that stealth can be maintained, such as if there is a lack of concealment or one must walk within earshot/close proximity of an adversary on potentially compromising surfaces like gravel or creaking wooden floors, then there is no longer any reason to move slowly in an attempt to maintain stealth. The advantage of stealth has already been lost, so it is perhaps better to make use of the advantages afforded by speed.

These are just some considerations on this topic that the present author felt were important. Ultimately, the choice of rapid or slow movement must be your own, as it is you who knows your situation best and who must live with any consequences that may result from such a choice. That said, however, do not allow yourself to be trapped in “paralysis by analysis.” Perhaps what is most important is to make a rational choice based on the information you have and to execute it with full conviction, though of course with the flexibility to change should new information or circumstances require.

Though in conclusion, overall, it seems that slow movement is probably the best default mode for civilian escape and evasion, changing to fast movement only in situations where it becomes more beneficial or necessary. Examples of when it would be advisable to adopt fast movement include when crossing an open area, when passing through a potential ambush site (though open areas and potential ambush sites should be bypassed if at all possible, thus eliminating the need for speed), when breaking contact with the enemy, when there is some compelling reason to reach the destination before a certain time as well as when avoiding detection through stealth is no longer feasible.

The last point about whether or not stealth is feasible, however, leads especially well into the next MOUT principle, namely:

Violence of Action-The fifth and final principle of MOUT is violence of action, which according to the Ranger Handbook, is comprised of “Eliminat[ing] the enemy with sudden, explosive force.” Obviously, in a self-protection scenario, engaging with and “eliminating” an enemy is far inferior to detecting and evading them prior to any such encounter ever having a chance to unfold.

Yet unfortunately, this ideal of avoidance cannot always be realized. There may be situations in which one is in very close proximity or is otherwise unable to avoid a direct encounter with an adversary. It is at times such as these that violence of action becomes crucial. But even then, the term “violence” may be too strong, since this term involves the use of force to intentionally damage, hurt or kill. Instead, we might speak more compassionately of being dynamic, committed, vigorous or energetic. This kind of directed and focused willpower is especially important in clearing urban spaces (which will be discussed in greater detail in the third article of this series) when such action is combined with speed and facilitates surprise.

Whatever terms we use, this may unfortunately come to involve weapons or the use of unarmed striking, grappling and escapes. There are also various objectives one may be seeking to achieve in carrying out such acts. These include breaking free from others’ attempts to physically capture/restrain oneself, preemptively attacking to distract, off-balance or incapacitate an adversary to facilitate one’s escape or to restrain an attacker, such as to facilitate the escape of others, prevent them from harming others and/or detain them until law enforcement can arrive.

Laws pertaining to the appropriate use of force in self-protection vary greatly between countries and also between localities within the same country. Thus, the reader is advised to familiarize themselves with the relevant laws in their own area as well as in areas where they may be travelling, but above all, to take every possible and reasonable measure to avoid the need to use force.

That said, when a clear threat has been positively identified, the decision to engage with the appropriate level of force must be made rapidly and executed immediately and with a level of vigor as if one’s life and the lives of one’s loved ones depend on it, because they very well may. To quote the Ranger Handbook again, this should be executed “with sudden, explosive force.”

Combining speed and violence of action increases the likelihood that one will be able to surprise the enemy, thereby depriving them of sufficient time to react.

Furthermore, it is not just physical violence of action that is required. For this to be successful, physical action must be backed up by a mental readiness to immediately and vigorously close with and neutralize the threat. On violence of action, the manual Combined Arms Operations in Urban Terrain states, “It is not limited to the application of firepower only, but also involves a soldier mind-set of complete domination.”[2]

Yet to reemphasize, before resorting to physical violence, it is essential to first know that there is a credible threat, then to exhaust all means possible to avoid or escape from that threat, or if there is any way possible, to diffuse the situation, and then only as a last resort, to respond proportionately to that threat, commensurate with the laws in one’s locality.

But now, having covered some basic guidelines and principles for operating in urban terrain, with an emphasis on stealth for escape and evasion, the next two articles will respectively focus on urban stealth movement outdoors and indoors, though there is actually much overlap between these two topics. Later articles will also address different aspects of operating in urban terrain, such as pertaining to surveillance detection and countermeasures.

Bibliography

Itoh, Gingetsu. Gendaijin no Ninjutsu. Trans. Eric Shahan. Charleston: CreateSpace, 2014.

Itoh, Gingetsu. Ninjutsu no Gokui. Trans. Eric Shahan. Charleston: CreateSpace, 2014.

Tanemura, Shoto. Ninpo Secrets: Philosophy, History and Techniques, 3rd Ed. Matsubushi, Japan: Genbukan World Ninpo Bugei Federation, 2003.

US Army, FM 3-06.11 (FM 90-10-1) Combined Arms Operations in Urban Terrain (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 2002).

US Army, FM 90-10-1 An Infantryman’s Guide to Combat in Built-Up Areas (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 1993).

US Army, SH 21-76 The Ranger Handbook (Fort Benning, GA: Ranger Training Brigade – United States Army Infantry School, 2011).

US Army, STP 21-1-SMCT Soldier’s Manual of Common Tasks Warrior Skills Level 1 (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 2009).

[1] These guidelines are largely drawn from, but have further expounded upon those found in the section 071-326-0541 “Perform Movement Techniques During an Urban Operation,” in US Army, STP 21-1-SMCT Soldier’s Manual of Common Tasks Warrior Skills Level 1 (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 2009).

[2] US Army, FM 3-06.11 (FM 90-10-1) Combined Arms Operations in Urban Terrain (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 2002), 3-24.