To finish this series on urban stealth movement, we turn to what is perhaps the most dangerous aspect of this topic: movement indoors. Such increased risk is due to the extremely close quarters as well as contained spaces involved, both of which make encounters even more immediate, exacerbate the problem of being detected audially (though while making it easier to detect others) and generally allow fewer options for escape and evasion.

In dealing with this topic, we present a couple of guidelines related to windows and then shift our focus to clearing techniques for the lion’s share of this article. Finally, we attempt to bring this series to a coherent closure with some ideas on further exploration and training.

Dealing with Windows

Windows allow us to see outside but they can also allow others to see us when we are inside. Thus, here we briefly discuss windows and how to observe through them or move past them while also reducing the chances of being detected from outside.

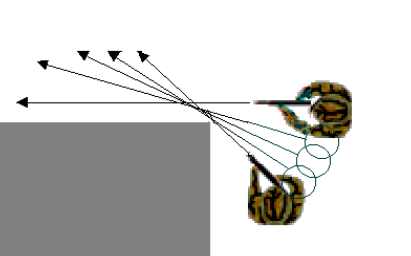

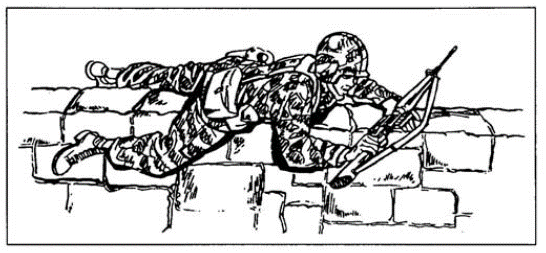

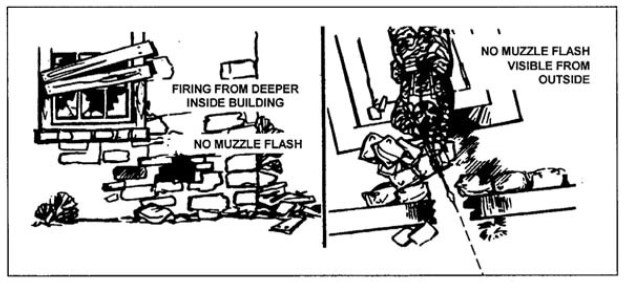

Observe through a window: When looking through a window from inside, stand back far enough away from it so as not to silhouette yourself to outside observers. In the below image, note the deeper position within the room and away from the window. If available, remain within shadows. Avoid tell-tale pulling aside of curtains or raising of blinds. Be certain that you are not backlit, that is, not having a source of light behind you to reveal your silhouette through the window or to cast a shadow on any blinds or curtains.

While common knowledge, it is important to be cognizant of the fact that if it is lighter inside than outside, it is easier for someone outdoors to see inside but more difficult for someone indoors to see outside. This is why for home security it is recommended to close one’s curtains or blinds before dusk. The reverse is of course also true: if it is darker inside than outside, then it is more difficult for someone outside to look inside but easier for someone inside to look outside.

Furthermore, correct usage of blinds, dependent upon which floor one is on (downward toward the outside on the first floor, but upward toward the outside on the second), help to increase privacy while also allowing one to observe outside and let light in.[1]

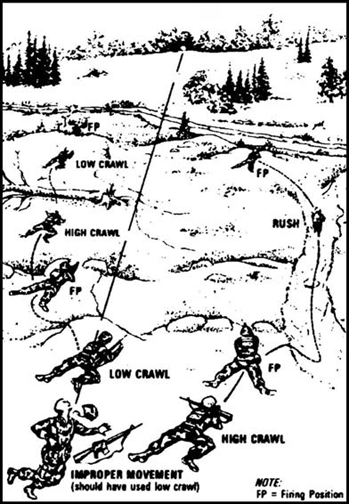

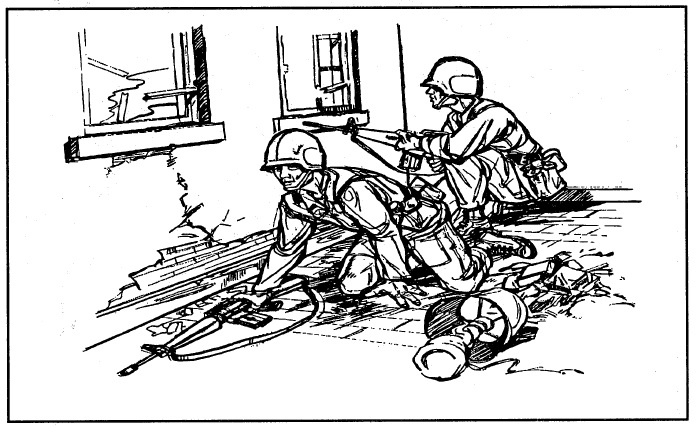

Move past windows: As with moving past windows outdoors, to prevent silhouetting oneself, it is best to either move back far enough away from the window that one cannot be easily seen from outside (esp. if on an upper floor) or to move under them. The latter can be done by crawling or using a crouched or squatting walk, as listed in the article Individual Stealth Movement.

Individual Clearing of Urban Spaces

Clearing urban spaces involves methodically searching areas to confirm or deny the presence of potential adversaries while being prepared to deal with or react to the presence of those adversaries accordingly as appropriate for one’s purposes. Since our purpose here is evasion and escape, the goal is to ideally move undetected to a safe place, detecting and evading any adversaries without them ever even being aware of your presence. Less than ideal would be to detect adversaries just before they detect you, which would give you a head start for flight or the advantage of the initiative if you must fight.

In a truly ideal situation, the need for clearing would be eliminated altogether by the preemptive security measures one has already taken at one’s home and workplace. These include, for example, ensuring that doors and windows are sufficiently sturdy and locked (especially at night), that there is sufficient exterior lighting, that vegetation does not provide intruders with concealment, that security alarms and video overwatch systems are installed and activated with placards displayed, etc. Following a reasonable home or workplace security checklist can greatly mitigate many risks. Nevertheless, no security plan is either foolproof or invulnerable, thus clearing is a skill worth honing.

All five of the principles for Military Operations in Urban Terrain (MOUT) discussed in the first article of this series; Surprise, Security, Simplicity, Speed and Violence of Action (S4V); come into play in such clearing. The main benefit of clearing is that it helps to deny the enemy the element of surprise and conversely, to ensure that you are not surprised. It can buy you precious seconds, or even a fraction of a second, that could mean the difference between life and death by alerting you to the presence of an adversary so that, if undetected, you can choose a different way out, or if detected, you can either immediately and rapidly initiate your flight/escape or aggressively move to dominate and gain the upper hand if you cannot flee and must fight. In either case, this is where preparedness for swift and decisive violence of action is imperative.

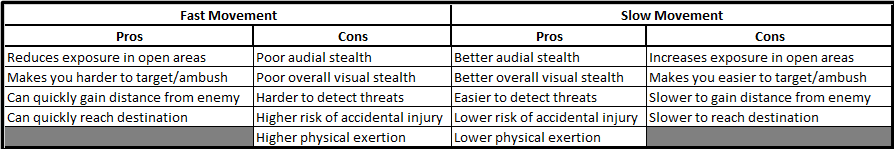

On the related topic of speed, as already discussed in the first article, for civilian escape and evasion, it is usually better to err on the side of caution and to proceed slowly unless there is some very compelling reason to move more quickly. Encountering an adversary is just such a case where speed, whether for flight or fighting, becomes crucial. So is passing through “fatal funnels,” as discussed below. Moving on to yet another principle of MOUT, the act of clearing is itself a method of maintaining security, ensuring that opponents are not within dead space that one is about to enter or pass by. Yet one must remember to frequently check one’s “six,” and indeed to maintain overall 360°-security (plus the third dimension of height—up and down), as opposed to being fixated with tunnel vision on just the space being cleared, thus losing situational awareness of that which is around you. Nevertheless, methodically clearing unseen space, one “slice of the pie” at a time, drastically simplifies your environment and limits the amount of information you have to take it at once as you gradually unveil new space.

Yet recall that the title of this article is “Urban Stealth Movement” and not “Urban Close-Quarters Combat.” These are two very different things. We may draw our fundamental skills, concepts and techniques from CQC/CQB, but our ultimate aim here is quite different.

It should be made very clear up front that you should never attempt to clear your home or any other space of potential intruders. The police should be contacted immediately if there is any serious suspicion of intruders, an active shooter or any other threats. They have the necessary equipment, training, personnel and resources to accomplish the extremely dangerous task of clearing with mitigated risk. It would be both foolish and irresponsible for you to attempt to do so on your own, especially single-handedly, since professionals almost invariably operate in teams, such as from around two to six people.

The only circumstances when you should be moving around and clearing spaces within a structure in which there are potentially hostile elements is while en route to 1.) exit the building, 2.) reach a place in which to barricade or 3.) locate group or family members like children or others who may be in danger and in need of assistance.

That said, realistically, it is understood that there may be cases when there is not yet any serious indication of intruders, perhaps while investigating a strange noise in the middle of the night, and one is only searching to confirm that the structure is secure. The clearing techniques discussed here can be used for such situations, but as soon as there is a confirmed or strongly suspected presence of an intruder, it is imperative to default to limiting oneself to the above three cases. Whatever the justification, if you do choose to go out clearing a structure, it is important to carry a cell phone with you as a means of communication with potential sources of aid as well as to remember that criminals usually operate in teams, so it is unlikely that there is only one intruder. Furthermore, remember that you have the advantage of intimate familiarity with the layout of your home or place of work, something the intruders probably lack. Thus, waiting quietly and listening may be substantially more valuable than even the best application of clearing techniques.

But to reiterate, unlike some military or law enforcement personnel, who may need to use clearing to secure entire buildings or to locate targets or criminals, the only time the private citizen should be conducting clearing with likely adversaries in a building is when they are looking for a way out of the structure or to a safe place within it to barricade in or to find someone else in need of aid to help them do the same. Do not go out to try to find the “bad guy(s).” This is not only unnecessary and extremely dangerous for you, but it also puts any loved ones you may have left behind in greater danger. It also puts you at risk of being mistaken for an intruder by the police.

Thus, if you return to your home and suspect that it has been entered by an intruder, do not enter and do not attempt to “clear” your home. Instead, call the police, stay on the line and wait for them to arrive while remaining somewhere in a safe place outside of your home.

If you are already inside your home and intruders break in, if you cannot with certainty leave quickly by another route without encountering them, then barricade yourself in place or in a designated and pre-prepared safe room (if you can quickly and safely reach it), call the police, remain on the line and stay where you are.

Again, do not go out in search of potential intruders yourself.

For the lone civilian seeking to make their way from a threat situation to a safe place, military or SWAT urban clearing techniques are generally not as helpful since, among other reasons, they typically involve teams of multiple individuals and are thus inappropriate for a single individual or a person with their family seeking to clear an escape route. Hence, it becomes necessary to rely on clearing tactics intended for single individuals, such as practiced by law enforcement personnel, who must sometimes secure urban spaces on their own (though even they seek to avoid doing so alone), or developed specifically for the purposes of single-person clearing.

Before proceeding any further, a brief disclaimer seems appropriate here. While the current author has been trained in military clearing methods on multiple occasions and has himself made use of clearing principles and techniques while moving through urban spaces in a combat zone, he is far from being a specialist in this area. He was in no way a “door kicker” with extensive experience in the topic at hand. Rather, this article is his humble attempt to bring attention to a valuable set of skills and knowledge that have hitherto been largely confined to military, law enforcement or intelligence professionals along with the gun enthusiast community. It seems, however, that there are potentially much wider applications, as discussed below, and we have sought to adapt these more specifically for escape and evasion, whether armed or unarmed. The assertions made here should thus be seen as working hypotheses. Any constructive criticism or further ideas are sincerely welcome.

Armed or Unarmed Clearing & Improvised Weapons

Remember that for our purposes, the objective of clearing is to find a clear route to escape or to reach and secure a safe room, not to find and apprehend/engage with an adversary, as it might be for military or law enforcement personnel. Nevertheless, one may indeed find oneself face to face with an adversary. In such cases, being armed may well be more advantageous than being unarmed.

But despite the prevalent association of clearing with the use of firearms, one may indeed perform clearing whether armed or unarmed. CQB provides insights and methods that are extremely useful even without a firearm, or any other weapon for that matter. Yet this valuable knowledge has largely remained confined to military, law enforcement and intelligence professionals as well as the firearms enthusiast community.

This is unfortunate, since there are many CQB concepts and skills that are quite useful for finding a clear escape route or securing a safe room that do not require a firearm and could even be easily taught to children without any need for reference to firearms. Moreover, there are many localities in which firearms are not legally accessible to the general population without extensive restrictions, if at all, not to mention persons who are ideologically opposed to the use of violence or lethal force, even to save their own lives. It thus seems senseless to not make this information available to a wider audience. At best, such clearing methods might allow one to detect an adversary before they have detected you and then change routes to avoid them. At worst, if already compromised, they can help to mitigate or avoid being surprised and afford precious time to react, whether through flight or fighting.

If one does choose to be armed, it should be noted that this does not have to be a firearm. It could just as easily be a non-lethal alternative like a taser or pepper spray or an improvised weapon like a baseball bat, shovel, broom handle, skillet, kitchen knife, wooden training sword (bokken, 木刀), or in fact, especially a flashlight, which may not only be used like a baton for striking, but could also be used to expose, startle and temporarily blind an assailant, thus particularly facilitating escape. Granted, a handgun, rifle or shotgun has substantially longer range and immediate profound effect when used properly as compared with most non-lethal and improvised weapons, but among other concerns, their effects tend to be more serious and permanent, the risk of collateral damage is significantly greater and their legality (not to mention the potential legal consequences of their use) varies by locale.

Whatever the case, it is essential that if you do choose to be armed, that the weapons be accessible to you but tools such as firearms or live blades should not be accessible to children who could be seriously injured or killed by their misuse. Also be certain that any weapon carried is indeed legal to carry and use for self-protection in your locality and know the situations in which its use is legally acceptable, such as in terms of proportional use of force. Firearms often require registration, so be certain that if you possess and use one that it is properly registered in your locality if required to do so and that you have the correct permits to carry it. Moreover, be thoroughly proficient and well-practiced in the use of any arms you intend to carry (such as putting in sufficient and regular hours at the dojo or at the shooting range in the case of firearms). Also make sure that those arms are properly maintained and are not likely to malfunction (such as by cleaning and oiling firearms regularly). Some are simpler and need less maintenance than others. Likewise, different weapons require different amounts of training, for instance, firearms require substantially more training and practice as well as knowledge about the relevant laws pertaining to possession and use than pepper spray.

Yet also extremely crucial, and indeed of paramount importance, is that if you choose to carry a weapon of any sort, you must be willing and psychologically prepared to use it should that become necessary, appropriate and legally acceptable in your locality. If you are not, then it may very well be taken away and used against you. In such cases, it would thus be better to go unarmed.

During the act of clearing itself, if you do choose to use a weapon, improvised or otherwise, it is important to avoid allowing it to protrude beyond corners, thus announcing one’s approach. Being trained and well-practiced in weapon retention, that is not allowing an opponent to take your weapon and use it against you, is also advisable. On a related matter, also consider how you intend to carry the weapon while clearing and how you intend to use it if that becomes necessary.

For instance, if using a bokken, broom handle or similar object, rapidly repeated thrusts rather than “cutting”/striking techniques may be more effective and beneficial, keeping the opponent at a distance and even increasing it by pushing them back with one’s thrusts. Perhaps the optimum positions for this purpose are those known in a certain school of traditional Japanese swordsmanship as as gedan no kamae (下段之構, “low-level posture”) and tosui no kamae (棟水之構, “ridge water posture”), since they allow for a clear field of vision from ceiling to floor while also being poised to preemptively attack by simply raising the wooden training sword, broom handle or similar object while stepping forward to thrust aggressively and repeatedly at any threat within range. Moreover, compared with other possible postures, it is much easier to avoid announcing one’s approach by allowing one’s weapon to protrude beyond the corner, thus giving away one’s presence prior to clearing around the corner.

Another consideration pertaining to weapons is that you do not want to be mistaken for an intruder by the police if they arrive on the scene. Thus, be certain that you are not moving around your house, especially not with a weapon in hand (improvised or otherwise), when the police arrive. Ideally, you should either no longer be inside the residence when the police arrive, or you should be barricaded in a safe room which they have already been informed of the location of telephonically via emergency services like 112 (EU) or 911 (US).

Before delving into the fundamentals of clearing, it is important to point out that it is possible to prepare your home to facilitate your clearing efforts. As pointed out by Brett in his article “How to Safely Clear Your Home,” motion sensor-activated lights can be beneficial and there are affordable security cameras that can be wirelessly linked to your mobile phone, thus allowing you to clear your home remotely without exposing yourself to greater danger. Similarly, the placement of mirrors and other reflective surfaces can facilitate seeing around corners and into other rooms before entering them. Moreover, furniture can be arranged so as to offer an open field of view to create as little dead space as possible and while also being used to deny adversaries the use of certain other areas of dead space and encourage them toward the “fatal funnel,” discussed below, where they are more easily seen.

Clearing Fundamentals

There are a handful of basic situations that serve as a foundation for all urban clearing methods and should thus be mastered. Nevertheless, very few structures can be reduced to only these situations, thus flexibility and adaptiveness are crucial. All of these fundamentals can and should be practiced regularly while moving about one’s residence and place of work. This can be as simple as employing these techniques in conjunction with one’s daily activities, but one should also devote special time and effort toward practicing these fundamentals with whatever weapons, improvised or otherwise, that one may be expecting to use. Here, we propose the following as an optimum set of fundamentals.

Corners

Doorways/Rooms

Hallways

T-Intersections

X-Intersections

Opposing Open Doors

Stairs

Multiple Doorways/Rooms

With these major fundamentals listed, we now discuss each in turn. From among these, clearing corners, “pie-ing the corner” or “slicing the pie” is the most fundamental of all and will be discussed first.

Corners: We have already touched on “pie-ing” corners or “cutting/slicing the pie” in the preceding article in this series and, as just noted, it is the foundational technique for clearing. Ideally, it may allow you to see an adversary before they see you, so that you can then choose another route to avoid them. Yet even if they do detect you first, visually or audially, it can provide you with precious seconds or even a fraction of a second within which to react, whether your choice, depending on the circumstances, is flight, fight or even freeze.

When pie-ing a corner, to allow maximum time to react, it is advisable to be as far away from the corner being pie-ed as reasonably and practically possible, thus creating a large “reactionary gap” within which to respond to threats. If your aim is to quickly overtake an adversary while unarmed, then it may be advisable to be somewhat closer, but distance is emphasized here given our preference for escape and evasion over engaging in close-quarters combat. In any case, be certain not to “crowd the corner,” getting too close to it and/or allowing parts of yourself or any weapon you may be carrying to protrude beyond the corner, thus undesirably announcing your arrival in advance.

One may lean in slightly or even quickly peek around the corner. To practice and to see how much of oneself is exposed while pie-ing, leaning in and/or peeking, one can practice with a full-length mirror (as recommended in the WikiHow article “How to Clear a Building with a Firearm”), treating the edge of the mirror as the apex of the corner. The same article also provides a useful partner exercise that involves both participants carrying a flashlight while pie-ing from opposite sides of the same corner. The first participant to see the other “wins” by shining the flashlight on them.

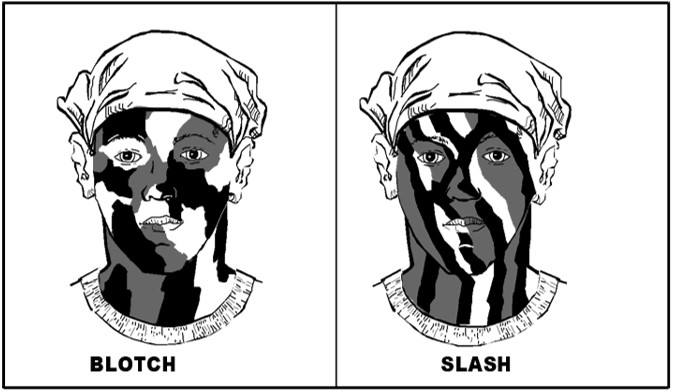

Regarding pace, in the best case, pie-ing along with all other clearing methods should be performed slowly and methodically, side-stepping without allowing the feet to cross and examining one “slice of the pie” at a time, scanning from floor to ceiling along the corner’s edge before stepping again to open up and allow you to examine another slice of the pie.[2] While doing so, whether unarmed or carrying firearms or improvised weapons, one should maintain a stance that both prevents one from being exposed prematurely around the corner (e.g., foot, shoulder, elbow, head or weapon) and also allows one to be prepared to engage with any threat that may present itself.

Such side-stepping, performed slowly and cautiously, is advisable (whether armed or unarmed) whenever possible, but especially if there is a high likelihood that there is an adversary on the other side. Sometimes, however, it may be necessary to clear more quickly. Thus, there is another, faster method that is valuable in situations when there is an urgent and compelling need to move more quickly. Yet this should only be done if there is only a limited possibility, with no specific indicators (such as having heard movement in a particular room) that an adversary is on the other side of the corner that is being “pie-ed.”

This quicker method involves walking in an arc, smoothly and with a lowered center of gravity, around the corner with the hips facing in the direction of movement while the head, eyes, arms and any weapons (improvised or otherwise and held in a defensive ready-position, prepared to engage potential adversaries) are oriented toward the center of the imagined circle and directed past the corner to see and be prepared to engage with whatever is beyond it.

This method is indeed used by military and law enforcement personnel, but the smooth, gliding and circular movements it entails with the upper body being oriented toward the center of that circle are also characteristic of the Chinese internal martial art known as Bagua Zhang (八卦掌, “Eight Trigram Fist”). Thus, though probably unintended, we might even add achieving a more fluid and structurally prepared pie-ing of the corner during urban clearing to the list of benefits that have been attributed to the practice of Bagua Zhang. Such smooth arcing movement is a recurrent theme in the fundamental clearing methods that follow.

Doorways/Rooms:

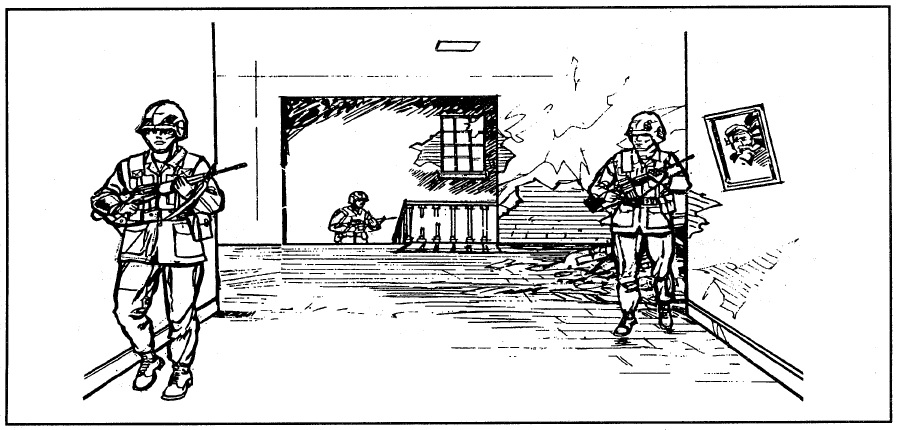

Since we are not clearing entire buildings to find adversaries, but instead seeking to avoid and elude them, it is only advisable to enter a room if it is absolutely necessary to do so as part of one’s escape plan, to locate an isolated group member or loved one or to shelter within that room (temporarily or for longer term). If the aim were to secure the building, this would be entirely unsound, as for this purpose, all rooms would have to be systematically cleared in the sequence in which they are encountered. Yet that is not our objective here, nor is it safe to attempt to do so on one’s own. Here we address four possible scenarios related to clearing doorways/rooms for evasion and escape: 1.) the door is open and there is no compelling need to enter, 2.) the door is open and there is a compelling need to enter, 3.) the door is closed and there is no compelling need to enter and 4.) the door is closed and there is a compelling need to enter.

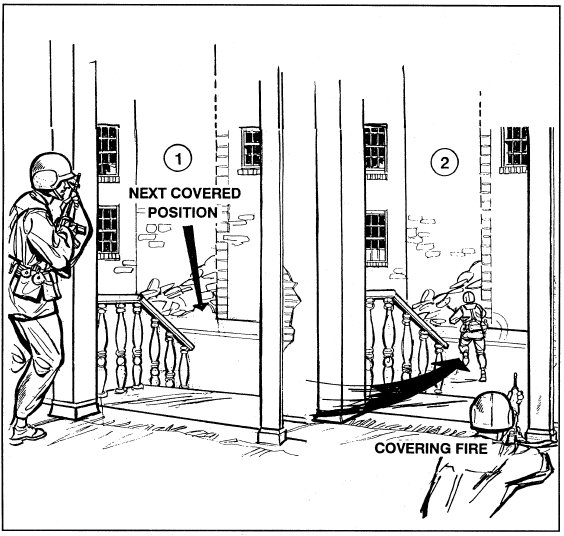

First, if a doorway is open and one must pass by it (without entering) as part of one’s escape route, it is advisable to perform a sweep from outside, arcing around the entrance while being as far away from it as possible/practical and visually clearing from outside. After doing so, one might pause and listen before proceeding further past the room to determine if one has been detected and if there are any adversaries in pursuit.

Second, if it is necessary to enter a room with an open door, such as as part of one’s escape route, to find a loved one or to shelter-in-place there, first sweep in an arc from the outside while peering into the room. There will be two narrow angles within the room to either side of the doorway that have not been cleared at all. From there, it is possible to enter the room directly at an oblique acute angle (diagonally) or to sweep back to the bottom of the arc before entering straight on at a 90-degree angle and stepping off toward either side of the doorway so as to move outside of the “fatal funnel” (discussed below), and then turning to first clear one direction and then turn again to clear the other.

Important to keep in mind is that, while many who practice and/or teach clearing treat an area as clear once it has been initially cleared, regardless of whether or not it is still under observation, the only time an area is truly clear is when one is directly observing it without obstruction and can continuously confirm the absence of an adversary. Sweeping cannot guarantee that an area which has been initially cleared remains clear after it is no longer under observation. This phenomenon has been described as the “floating angle.”[3] Sweeping back to the bottom of the arc to enter the doorway at a 90-degree angle can somewhat help reduce the risk involved with the floating angle.

Upon entering the room, if possible, it is probably best to first go in the direction away from the door itself, allowing one to clear the largest percentage of the room easily and quickly through a short period of scanning and then dealing with the small amount of blind space behind the opened door. With “center-fed” doorways, when the doorway opens up into the center of the room, this is more of an issue than with “corner-fed” doorways, when the portal is in one of the room’s corners, thus providing less space for adversaries to conceal themselves within behind the opening door.[4]

While stepping beyond the threshold to make the turn/entry into the room, glance quickly over one’s shoulder to look in the opposite direction of one’s movement to check any uncleared space there before returning attention to the path ahead and then spinning back around to face the direction one glanced toward. If there was anyone in the uncleared angle, or who moved within the floating angle during the sweep, you will see them during the glance and will thus be prepared to turn around to deal with the threat or know to flee. Be certain to also clear any dead space deeper within the room, such as behind furniture, appliances and curtains.

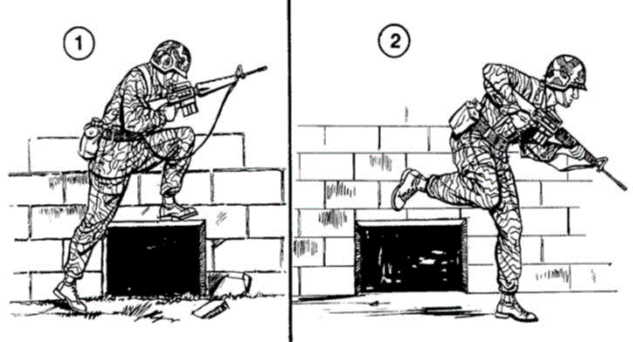

Whether one chooses to sweep slowly or hastily, it is always important to move through the doorway, which is the most common example of a “fatal funnel,”[5] as quickly as possible. This is a textbook example of a choke point and thus an ideal ambush site. Stepping through a doorway and into a room is where speed and violence of action come especially into play. If an adversary is inside the room waiting to ambush you, you are most accessible and predictable and thus easily targeted when you walk through the doorway. Just as with any templated ambush site, your goal in moving through a doorway is to move off of the “X” as quickly as possible.

Conversely, avoiding being in the fatal funnel can also be used defensively, while barricaded in place instead of moving around and clearing. If an active shooter, for instance, enters the room you are sheltered in, it is best to not be in the fatal funnel where they will see you immediately upon entering. Instead, it would be far better to remain within one of the angles of dead space not within the fatal funnel and to the side of the entrance (the areas that remain uncleared even after sweeping from the outside). This affords you the element of surprise and the ability to essentially flank the intruder by ambushing them from the side as they enter.[6]

Third, if a door is already closed and there is no reason to enter the room, then it is advisable to simply pass it, stealthily and without attempting to enter.

Fourth and finally, if it is indeed necessary to enter a room with a closed door, such as to escape through that room, to find a loved one or to barricade there, it is first important to determine whether the door opens inwards or outwards. If you can see the hinges, then the door opens outwards, towards you. If you cannot see the hinges, then the door opens inwards, away from you. If the door opens outwards, it is advisable to open it from the hinges side. Conversely, if it opens inwards, it should be opened from the doorknob side. In both situations, this avoids an immediate encounter and allows the door to act as momentary concealment (though probably not cover from bullets).[7]

In either case, it is important, after swinging the door open, to immediately step back and away from the doorway. This has been referred to as “ghosting,”[8] since from the perspective of anyone who may be inside the room, it appears that the door has opened on its own, as if by a ghost. It is important to swing the door open with enough force that it opens fully, but not so much that it bounces back and closes again. Once this has been done, one proceeds precisely as when entering a room with an open door as described above, starting with performing a sweep from outside before entering as before, but with an especially heightened awareness that one has certainly lost the element of surprise by opening the door and any adversaries within are already anticipating one’s entrance.

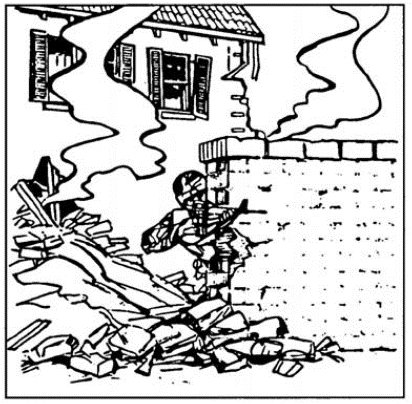

Hallways: There are differing perspectives on how to move through and/or clear hallways. Some experts advise hugging the wall while others recommend remaining in the center, between the two walls.

According to the former perspective, just as when moving parallel to buildings if outdoors, when indoors and moving through a hallway, it is advisable to stay close to one wall or the other. The logic goes that this is to avoid remaining in the more readily seen and engaged center of the hallway, which is a natural focal point that we might consider a kind of “fatal funnel.” Nevertheless, hallways in their entirety could be considered fatal funnels in and of themselves, which is why it is inadvisable to linger in them, just like we limit time in the doorway when clearing rooms.

According to the latter perspective, however, since ricocheting bullets tend to hug the walls, one should remain more in the center, between the two walls, to reduce the risk of being hit by such ricocheting rounds. The further benefit of being in the middle is that it allows equal observation of both sides of the hallway to identify upcoming doorways and whether or not those doors are open or closed.[9]

Whichever approach you choose to take, it is advisable to limit the amount of time you spend in hallways, since there are at least two avenues of approach and there may also be multiple doorways and corners from which an assailant might suddenly appear. Thus, do not loiter in hallways. Use them only as routes to escape to a safe place or find a group member or loved one. If you need to pause your escape to regroup, plan, prepare or administer emergency first aid, occupy and barricade a room temporarily, before returning to the hallway to proceed with escaping, etc. If escape is not possible and barricading is the next option, this should of course be done inside a room rather than a hallway.

If there are open doors in a hallway that you are passing through, these can be partially cleared by performing an arced sweep as you pass by them. This would not be tactically sound at all if one’s aim were to clear the entire building. If this were the goal, then it would be necessary to systematically clear each room in the order in which they are encountered, whether the doors are closed or not. Yet given our objectives of escaping, reaching a safe room or locating an isolated group member or loved one, then foregoing clearing each room is probably advisable.

T-Intersections: Clearing t-intersections is very similar to clearing a doorway. When approaching a t-intersection, determine which direction you want to go, right or left. Imagine a straight line drawn between the two corners. We will refer to this as the “threshold.” If you choose to go right, for instance, then “pie” the left corner first, but without passing beyond the threshold at the right corner to avoid exposing oneself beyond the right corner. Then, sweep in an arc toward the left corner while pie-ing the right corner, again, not crossing the threshold at the left corner. In both directions, there will be two narrow angles that have not been cleared at all (not to mention the above-noted concept of the “floating angle”). Step beyond the threshold to make the right turn, but while doing so, glance over the left shoulder (or the right shoulder if turning left) to check the uncleared angle there before returning your attention to the path ahead. If there was anyone in the uncleared angle, or who moved within the floating angle after you moved to pie the right corner, you will see them and can thus turn around to face the threat or know to flee.

X-Intersections: Dealing with x-intersections is basically the same as negotiating t-intersections, with the notable exception that there are four possible avenues of approach rather than just three. Thus, while clearing left and right or right and left and also paying attention to one’s “six,” one must also pay attention to this fourth avenue of approach. Moreover, if you choose to go straight instead of turning, be certain to glance in both directions while crossing through the intersection to check the small angles on either side that were not cleared during the sweep.

Opposing Open Doors: This situation is treated quite similarly to the preceding x-intersection. Here it is likewise possible to either go straight or to turn, left or right. So if while moving through a hallway, one encounters two open doors that are opposite one another, visualize an imaginary threshold just before both doorways. Then conduct a sweep as you would with an x-intersection.

If you intend to go right, first clear the left angle, then sweep to clear the right angle and quickly glance to the left while crossing the threshold and entering the room to the right as you would enter any room, but without the benefit of a full outside sweep. Conversely, if you intend to go left, first clear the right angle, then sweep to clear the left angle and glance to the right before crossing the threshold and entering the room to the left.

If you intend to go straight and pass both rooms, however, glance left and right as you pass both doorways. It may be advisable to turn around and pause after passing both doorways to listen and observe to know if you have been detected and if it is necessary to increase speed to escape or to engage with a pursuer.

Stairs: Clearing staircases is like slicing the pie, but done continuously while spiraling upwards or downwards to ascend or descend a series of steps. Yet it is even more complex than that, because as one moves, there are multiple angles where dead space is being gradually or suddenly revealed. This includes the stairs themselves (a diagonal corner), the next landing (a horizontal corner) and whatever type of area the stairwell is in, whether enclosed and accessible through a doorway or opening up directly into another area (generally a vertical angle) such as a hallway or lobby (which entails a deeper area to clear as well as likely obstacles within it that create additional dead space).

Multiple Doorways/Rooms:

When there are multiple rooms with closed doors, the situation is substantially simpler than if the doors are open. Be aware of these other potential avenues of entry and prepared to respond if an adversary comes through one of them, but do not open the door and enter unless necessary for escape, etc. If the doors are already open, things become much more complex. It is then best to deal with whichever doorway/room one has encountered first, but while doing so, striving to use one’s clearing movements for that doorway/room (whether the outer sweep before entering the room or after entry while clearing deeper within the room) to simultaneously also clear as much as is possible of adjacent rooms with open doors. In situations with multiple open doors, Special Tactics LLC advises using speed as one’s security to move to more advantageous positions.[10]

Conclusion

To bring this three-part series on urban stealth to a close, in review, we began with some general guidelines and principles of operating in urban terrain in the first article followed by exploring some specific ideas for movement outdoors in urban settings in the second article as well as indoors in this third and final article. These articles assume a basic underlying knowledge of stealth generally, whether in urban or rural terrain, which were addressed in the four-part series on the fundamentals of stealth. We have drawn from or touched upon a variety of sources, especially from military and law enforcement, as well as parkour, climbing and mountaineering, which are themselves fulfilling pastimes and effective forms of physical exercise, thus making their pursuit worthwhile endeavors in their own right. Yet there are still other pursuits, skills and areas of knowledge that could also be incorporated into developing viable approaches to stealth for escape and evasion in urban settings. These might include, for instance, paintball, lasertag or video games, which could offer new approaches to training, techniques and strategies. An excellent example is the works of the video game enthusiast YouTuber Stealth Technique. Finally, we must note that there is still much more that could also be addressed in relation to this theme. For instance, here we have dealt with preventing one’s physical form from being discovered and have not at all touched upon the concept of “going gray,” surveillance detection and countermeasures or the issue of stealth/privacy in cyberspace. These will be dealt with in future articles.

Bibliography

Brett. “How to Safely Clear Your Home.” ArtofManliness.com. July 11, 2022, https://www.artofmanliness.com/skills/manly-know-how/safely-clear-home/.

Denning, Jeffrey. “Room Clearing 101: Five Things You Should Know About Close-Quarters Combat.” Guns.com. March 17, 2022, https://www.guns.com/news/2012/05/08/room-clearing-close-quarters-combat-battle.

Feildboy, Eliran. “ITCQB | One Man Room Clearing Tactics.” UFPro.com. March 17, 2022, https://ufpro.com/us/blog/itcqb-one-man-room-clearing-tactics.

GunSpot. “Avoid the Fatal Funnel: Surviving a Home Invasion.” TheArmoryLife.com. 05 May 2022, https://www.thearmorylife.com/avoid-the-fatal-funnel-surviving-a-home-invasion/.

Sam. “Why No CQB Home Defense? Because You’re Untrained Stupid.” Spotter Up: In Depth Tactical Solutions. March 17, 2022, https://spotterup.com/why-no-cqb-home-defense-because-youre-untrained-stupid.

Something Kind. “Adjust Venetian Window Blinds: Privacy, Light.” YouTube.com. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h5PBtWd4YgY accessed 29 June 2022.

Special Tactics, LLC. Single-Person Close Quarters Battle Urban Tactics for Civilians, Law Enforcement and Military (Special Tactics, LLC, 2016).

Suarez, Gabe. Tactical Advantage: A Definitive Study of Personal Small-Arms Tactics (Boulder, CO: Paladin Press, 1998).

US Army, FM 3-06.11 (FM 90-10-1) Combined Arms Operations in Urban Terrain (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 2002).

US Army, FM 90-10-1 An Infantryman’s Guide to Combat in Built-Up Areas (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 1993).

US Army, SH 21-76 The Ranger Handbook (Fort Benning, GA: Ranger Training Brigade – United States Army Infantry School, 2011).

US Army, STP 21-1-SMCT Soldier’s Manual of Common Tasks Warrior Skills Level 1 (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 2009).

Wagar, Nathan. “CQB and the ‘Floating Angle’.” Borderland Strategic. March 17, 2022, https://borderlandstrategic.com/2017/06/13/cqb-and-the-floating-angle/.

wikiHow. “How to Clear a Building with a Firearm.” wikiHow. March 17, 2022, https://www.wikihow.com/Clear-a-Building-with-a-Firearm.

[1] For a helpful demonstration, see Something Kind, “Adjust Venetian Window Blinds: Privacy, Light,” YouTube.com, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h5PBtWd4YgY accessed 29 June 2022.

[2] For a more detailed discussion of angles in clearing and the correlation between increasing angle width and increasing exposure/risk, see Eliran Feildboy, “ITCQB | One Man Room Clearing Tactics,” UFPro.com, March 17, 2022, https://ufpro.com/us/blog/itcqb-one-man-room-clearing-tactics.

[3] For more on this, see Nathan Wagar, “CQB and the ‘Floating Angle’,” Borderland Strategic, March 17, 2022, https://borderlandstrategic.com/2017/06/13/cqb-and-the-floating-angle/.

[4] For a detailed treatment of dealing with “center-fed” versus “corner-fed” rooms, see Special Tactics, LLC, Single-Person Close Quarters Battle.

[5] For a useful explanation and demonstration, see the following article and accompanying video: GunSpot, “Avoid the Fatal Funnel: Surviving a Home Invasion,” TheArmoryLife.com, https://www.thearmorylife.com/avoid-the-fatal-funnel-surviving-a-home-invasion/ accessed 05 May 2022.

[6] For a helpful explanation and demonstration, see Reflex Protect, “What is the ‘Fatal Funnel?’,” YouTube.com, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s-rTPf_uWNg accessed 05 May 2022.

[7] Special Tactics, LLC, Single-Person Close Quarters Battle, 17.

[8] Brett, “How to Safely Clear Your Home.”

[9] Special Tactics, LLC, Single-Person Close Quarters Battle, 58.

[10] Idem, p. 76.