Whether by camouflage, concealment, deception or some combination thereof, the goal when practicing stealth is to prevent an observer from perceiving what we are calling “recognition factors” or “target indicators” of oneself, one’s equipment or one’s position, whether those indicators are direct or indirect. In his 1937 work Gendaijin no Ninjutsu (“Ninjutsu for the Modern Person,” transl. Eric Shahan), Itoh Gingetsu presents stealth, which he sees as the definitive aspect of ninjutsu, as a practical means of self-protection in the modern era. The present article agrees with him on the point that stealth can indeed serve as a viable means of self-protection, but it also echoes much of the same approach. Itoh describes a progression of “six non-existences” (roku mu) to be aspired towards, which he describes in detail under the headings of mu shoku (“colorless”), mu kei (“shapeless”), mu seki (“trackless”), mu sei (“voiceless”), mu soku (“breathless”) and mu shu (“odorless”). In this listing, one can discern both direct and indirect target indicators as well as the categories of visual, audial and olfactory, and as with Itoh, our aim is to disguise, eliminate or draw attention away from such recognition factors.

Because of our focus on practical evasion for civilians for self-protection rather than, for instance, conducting military operations, we are not concerned with aerial observation or with recognition factors that apply to more sophisticated threats, such as thermal or radar signature, etc., but instead with those factors that are detectable by the natural unaided senses. Out of the five senses, those we are most concerned about with regard to stealth, in order of precedence, include: sight, hearing and smell. Therefore, the target indicator categories discussed below are divided into three types of direct target indicators (visual, audial, olfactory) along with indirect target indicators. We now begin with direct visual target indicators.

Visual Target Indicators:

Vision is the most dominant of the human senses and the speed of light is substantially faster than the speed of sound. For some idea of how great that difference is, “light travels 186 thousand miles in 1 second, while sound takes almost 5 seconds to travel 1 mile.”[1] Yet it is not so much the speeds of light and sound that matter to us, since the time difference is basically negligible for our purposes, but rather the distance that they can travel. But this varies and relies greatly on the source of such light or sound along with environmental factors, though we offer some examples. Hopefully these will provide some perspective as to why we pay so much attention to visual target indicators, which we discuss below under the categories of color, contrast, texture, shine, light, shape/silhouetting, shadow, dispersal/spacing and movement. To our benefit, however, low light conditions as well as precipitation, fog, dust clouds or other weather factors can severely reduce visibility, thus helping us to successfully avoid being detected. Conversely, daylight and clear weather make stealth more difficult to achieve. Furthermore, the concealment provided by terrain, vegetation and man-made features are also considerable assets. Flat terrain with little or no vegetation or buildings offers fewer opportunities, but topographically varied terrain and areas with substantial vegetation and/or man-made structures provide a plethora of possibilities for stealth. But now, we delve into the various visual recognition factors individually, beginning first with color.

–Color: Utility workers may wear bright colors like neon orange to attract attention and avoid visually blending into their environment so as to remain safe by alerting passing motorists to their presence. Likewise, signal panels may also be brightly colored to attract attention from search teams and rescue aircraft. When eluding an assailant, however, it is desirable to do the opposite, wearing colors that blend well into one’s environment, such as subdued drab greens and browns when in a forest, tans in the desert or white in snow. But what if one is not already wearing the perfect color to fade into their background? The situation is not as bleak as it may seem.

There is always the option of relying on concealment more than camouflage, but beyond that, differences in color are only most important in daylight, at closer distances and in environments dominated by a single color, such as in the case of snow and deserts. Conversely, color is less important of a factor in low light conditions and at greater distances. From a long range, colors tend to blend together for the observer into a single tone. Since in darkness, the human eye relies on rods, which do not perceive color (instead of cones which do), this becomes less important. In the image below, a neon orange safety vest has been placed only a single layer of foliage deep within a bush.

This color photo was taken in daylight, but when the same photo is converted to black and white, the bright orange vest blends with and becomes almost indiscernible from its environment. This illustrates how darkness and the accompanying lack of color vision makes color a much less significant concern. Nevertheless, the next recognition factor of contrast does retain some importance in low light conditions.

–Contrast: Although our vision in darkness does not perceive different colors, it can detect variations in shade, which we are referring to here as contrast. For instance, even at night, contrary to common depictions in popular fiction, black is rarely if ever a color that blends well with any environment. It instead usually stands out as anomalous, being too dark in shade to match its surroundings. Hence, black or white and other very dark or very light shades of color tend to stand out. This risk, as well as the risk of exposure associated with any non-matching colors in general, can be 1.) eliminated by completely concealing such colors, 2.) reduced by changing the color itself to more closely match the environment, such as with paint or dye (though this can be time-consuming and impractical for short range self-protective evasion), or 3.) mitigated by partial concealment and camouflage. By way of illustrating the third option, the figure below features two balled-up pieces of fabric, one white and the other black. In three successive images, they are placed first superficially on the outside of a bush, then within the bush just behind the outer wall of foliage and finally deeper inside the bush.

Note how being placed behind a layer of foliage partially conceals the black and white pieces of cloth, but it also alters their texture and shape (two further recognition factors discussed below). Moreover, placing the pieces of cloth deeper within the shadows of the bush also makes the contrast less of an issue. By doing this, the shadows make the lighter color (white) appear darker, making it more closely match its environment for the observer, while the surroundings of the darker color (black) also appear darker, thus also reducing the concern about contrast from being too dark.

–Texture: Despite comparable colors or shades, surface textures may also vary, such as being smooth, rough, leafy, grassy, etc. For example, the below image features foliage with two only slightly different shades of green, but with quite different textures, one leafy and the other grassy.

A tiger’s stripes, for instance, help it to remain undetected from its prey while it stalks through tall grass or jungle foliage by mimicking the texture of the surrounding vegetation while also disrupting the tiger’s overall shape (shape being another indicator discussed below). When employing stealth as a self-protection measure, however, it is unlikely (though certainly not impossible, such as if engaging in outdoor sports that also involve stealth) that the clothing one happens to have on when needing to vanish from observation will blend perfectly in terms of texture. Yet given that this recognition factor is only noticeable at quite close ranges, it may be less of a concern once substantial distance from the enemy has been achieved and is not expected to be lost. Thus, one might choose to accept risk over spending a longer amount of time on improving the texture of one’s camouflage. As seen in the above images with the neon orange vest or pieces of white and black cloth in a bush, being behind just a single layer of foliage can substantially alter texture (as well as shape).

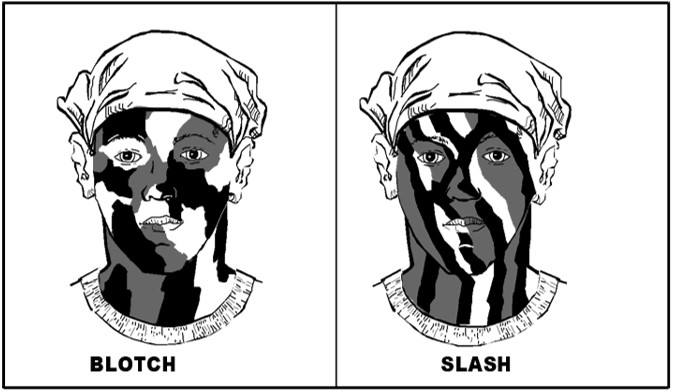

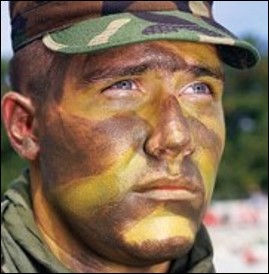

If a closer encounter and scrutiny are a concern, however, one may attempt to mimic the texture of their surroundings by adding natural or artificial material, like branches with leaves, grasses or strips of burlap cloth. Likewise, camouflage paint can, alongside blending by altering color and shape and reducing shine, also mimic the texture of the environment. A blotch pattern could be used in a deciduous forest and a broad slash pattern could be used for coniferous or jungle settings or a thin slash pattern for blending into tall grass.

–Shine: This refers to the reflection of light off of exposed skin (regardless of how dark one’s skin tone, since all skin secretes oil) or reflective surfaces one may be carrying, such as glasses, watches, jewelry, signal mirrors, etc. To understand the significant risk of discovery posed by shine (but also the significant hope of rescue if using shine as a means to signal for aid), a 3×5-inch signal mirror has a surface-to-surface range of ca. 10 to 16 km (6 to 10 miles). This range is actually only limited by the curvature of the earth and surface-to-air signaling with such a small mirror can go up to 32 kilometers (20 miles).[2]

For stealth purposes, sources of shine can be covered, removed or subdued. Exposed skin can be covered with clothing or painted. Another approach to camouflage face paint which is specifically focused on eliminating sources of shine and is also used when one has only a single dark shade of paint (such as when using charcoal or burnt cork as improvised face paint) involves applying such paint to protruding areas like the brow ridge, nose, cheekbones and chin. Watches and jewelry can likewise be covered or can be removed altogether. If one must wear glasses, it is possible to lightly coat them with dust to reduce shine. If carrying a signal mirror, when not in use, have the reflective side facing the body inside one’s pocket.

–Light: Artificial sources of light; like flashlights, headlamps, cell phone displays and cigarettes; can be used carelessly and haphazardly and may be seen from substantial distances. The judicious and cautious use of such sources of light is referred to as “light discipline.” This is quite significant when considering the potential risk of exposure entailed in their use since, for example, with no obstructions from terrain and vegetation, a lit cigarette can be seen from as far as 5 kilometers (ca. 3 miles) away. To help limit the use of a flashlight for map checks, be familiar with your area of operation and the selected route to your destination. When performing map checks with a flashlight, it is advisable to do so under a thick covering like a blanket to reduce the amount of light that escapes. On a further note, while using a red lens with a flashlight preserves night vision, a blue-green lens is more difficult for observers to detect. Most cell phones can also be switched to a darkness mode, which helps to reduce the amount and intensity of light produced.

–Shape/Silhouetting: The shape, outline or silhouette of one’s body or parts thereof, especially the head and shoulders, as well as equipment can present a unique signature that may reveal one’s presence and should thus be disguised or concealed. It is of course possible to use camouflage material like branches and grass attached to one’s clothing and headgear to break up one’s shape. Moreover, as described above when discussing texture, disruptive camouflage, like blotch versus slash patterns or the striped pattern of a tiger, also distort or break up shape. Yet as already noted, these take time, effort and attention to apply and maintain, thus it may be preferable to simply be cognizant of how one’s shape/silhouette interacts with (is concealed or highlighted by) one’s environment and to take some basic precautionary measures.

It is important to be aware of one’s background from the perspective of an observer. Situations where one’s outline contrasts dramatically with their background, such as being silhouetted against the sky or backlit while looking out of a window, should be especially avoided.

Crouching, squatting, kneeling or laying prone while static or moving reduce and alter or completely conceal one’s silhouette, as contrasted with standing upright without appropriate concealment, which is much easier to see and recognize.

Making use of the “military crest” of hills not only helps to prevent silhouetting, but it can also facilitate your own ability to observe. Being on the reverse slope of a hill (the side away from where any adversaries are believed to be) offers concealment by way of the terrain itself, whereas when on the forward slope (the side facing where the enemy is thought to be), one must rely on camouflage or use vegetation, rocks or manmade structures for concealment.

When observing from behind concealment, it is always desirable to avoid silhouetting oneself by looking through, under or around (and low to the ground), as opposed to looking over. Yet wherever one observes from, it is always preferable to do so with a suitable background and from behind additional concealment such as foliage.

The same principle just discussed regarding observing from behind concealment (through, under or around [and low to the ground] as being preferred to looking over) applies to negotiating obstacles. When passing obstacles, going through, under or around (and low to the ground) is preferred as it is less likely to expose and highlight one’s silhouette than moving over top of them. When it is necessary to go over, such as crossing over a wall, fence or a hilltop or ridgeline, it is best to remain as low and flatly pressed to the obstacle as possible to reduce silhouetting. It is also best to do so at a place that offers camouflage and concealment, such as provided by foliage and shadows.

One pre-emptive deception measure for crossing over obstacles like hills, where one’s silhouette may have been exposed, is to change the direction of one’s movement after crossing. Any observer losing sight of oneself after crossing the obstacle will be led to believe that one has continued in the previously established direction of movement. Additionally, if at any point one drops to a crouched, prone or kneeling position to avoid enemy observation or fire, it may be advisable to move; such as by rolling, crawling or using squatting movement; before raising one’s silhouette again, if the adversary may have been observing the last known place where one’s silhouette was exposed.

–Shadows: Shadows can be both a hindrance and a substantial aid in terms of camouflage. We begin with the former. The shadow that one projects can announce one’s presence in advance of one’s arrival, such as around a corner, thus one must be cognizant of where their shadow is being projected and how it could reveal their presence to an observer. Shadows, such as from the brim of one’s hat, can also present a distinctive and compromising appearance. Solutions to the brimmed hat problem could be to remove them or simply not wear one in the first place, turn around front-billed caps or select headgear without a brim.

But for an example of another response to potentially compromising shadows, one which can be drawn from nature, a number of animals and insects; including some gazelles, sharks, penguins and caterpillars; have evolved coloration patterns that make use of something known as countershading, featuring lighter underbellies which would otherwise be darkened by shadows. Countershading thus seeks to counteract the compromising effects of shadows by reversing the shading scheme so that the underside is actually lighter instead of darker. This has been employed by modern militaries in camouflage paint schemes for their equipment, such as for aircraft and artillery pieces.

A similar principle is also at play in yet another approach to applying face paint camouflage, one which pays more attention to reversing the effects of shadows than to texture. Herein, darker paint is applied to protruding surfaces like the brow ridge, nose, cheekbones and chin (as discussed above with regard to reducing shine), while lighter paint is applied to sunken or otherwise shaded areas like the eye sockets, hollows of the cheeks, under the lower lip, etc.

But aside from shadows being potential recognition factors, they can also offer a significant means of reducing such indicators. In fact, in the absence of complete concealment, hiding within shadows is the next best thing, since other visual recognition factors, like color, contrast and texture, can also be significantly reduced or even eliminated. Thus, when selecting a hiding place, look for shadows, the darker and deeper the better. The below image illustrates how even when wearing clothing that differs considerably from one’s environment in terms of color, contrast and texture and without making any attempt whatsoever to hide, simply stepping back into the shadows can help to reduce how apparent one appears to an observer. Thus, when actually attempting to hide, being in the shadows (again the deeper and darker the better) substantially improves one’s chances of avoiding detection.

Given this, during evasion it is advisable to habitually remain within the shadows whenever possible. This includes staying in shadows when moving, or we might say, following the “shadow trails.”

–Dispersal/Spacing: If travelling as part of a group, spreading out moderately makes smaller, dispersed targets for the adversary to detect, in contrast to a more easily detected larger mass bunched together. Yet dispersal should not be so far apart that members cannot see and communicate with one another, thus preventing the leader from controlling the element and risking group integrity by increasing the likelihood that members become separated from the group. The appropriate distance for any given circumstance is primarily determined by the visibility afforded by terrain and weather. The US Army manual Infantry Platoon and Squad states that a “unit should be dispersed up to the limit of control,” but describes a normal spacing between individual patrol members as being 10 meters.[3] Yet poor visibility due to dense vegetation or inclement weather requires closer spacing.

Other factors, however, include maturity and whether or not all members of the group are well-trained and accustomed to operating together. Young children and people less (or un-)familiar with patrolling techniques and the standard procedures of the group must not be dispersed too far. Such individuals could be paired with more experienced and mature group members and instructed to follow closely behind their senior partner and to do what they do, halt when they halt, take a knee when they do, move into a prone position when they do, etc. If there is a larger number of children or less experienced group members, then dispersal must be sacrificed and the associated risk accepted in order to ensure group integrity so that no one is left behind or separated from the group.

–Movement (as it pertains to visual detection): Oftentimes before any other visual recognition factors can be noticed, it is movement, especially when it is sudden, rapid and erratic, that attracts the attention of the human eye. Thus gradual, slow and smooth movement is preferred as it is less easily detected. Movement should also be very deliberate and preplanned, as haphazard selection and use of routes and movement techniques can easily lead to mistakes, accidents and exposure. Furthermore, limit movement to only when it is absolutely necessary. Freezing is an ingrained natural response that serves us well in avoiding detection from threats.

When it is indeed safe and necessary to move, know your next destination and proceed there only after taking care to select concealed or at least camouflaged routes. Also, keeping the use of movement techniques proportionate to the concealment provided by one’s environment is crucial to maximizing efficiency. Use movement techniques which, to a degree proportionate to one’s environment and the risk of detection, lower the silhouette and help one to remain behind concealment. When one’s entire body is already concealed from the enemy – so long as one has a good idea of where the enemy actually is – crouching, kneeling or crawling do not make sense and are too costly in terms of time and energy expended. When moving across areas with limited opportunities for concealment, it is advisable to dart in 3-5 second rushes between positions of concealment to reduce the likelihood of being observed. For an overview of individual movement techniques, see the earlier article entitled “Individual Movement Techniques.”

Additionally, it is also helpful to know that movement which is lateral in relation to an observer is easier to detect than moving straight toward or away from them, as illustrated in the image below.

On a final note about movement in relation to visual recognition, causing surrounding vegetation, such as tall grass and branches, to also move can reveal one’s location and should thus be avoided. Movement as it relates to audial detection is also treated below as one of the audial target indicators, the topic to which we now turn.

Audial Target Indicators: Noise discipline

Generally speaking, after visual recognition factors, audial target indicators are the next most important concern for maintaining stealth. Speech, breathing, equipment one may be carrying or using and moving and interacting with one’s environment can all produce sound that could compromise one’s whereabouts. We address each of these factors below in greater detail, but we will first outline some general considerations about the relationship between, on the one hand, sound, and on the other, weather and terrain.

Just as how weather conditions can help or hinder attempts to conceal oneself visually, it is possible and advisable to mask the sound of one’s movements with natural sounds like wind, thunder, precipitation or running water, but also with the sounds of traffic and other urban noise. Moreover, movement is quieter when vegetation and soil are moist but not saturated, whereas crushing dry leaves underfoot or sloshing through puddles of water produces considerable noise. Urban environments can likewise present notable advantages and disadvantages, whether predictable pavement and tile floors or compromising gravel and creaking floorboards, stairs and doors.

Another crucial consideration is the fact that sound travels faster in the cold, such as at night and/or over bodies of water. Additionally, observers may be paying greater attention to their other senses at night or in darkness, due to the degraded visibility in such low-light conditions, and they may therefore be more attuned and sensitive to any noises one may produce.

Obstacles like buildings, vegetation and terrain features can present barriers to sounds you may produce, thus audially concealing you. But conversely, the acoustics may also work against you. Echoes, or the lack thereof, are another important facet to consider. Echoes can highlight one’s presence, since they reverberate the sounds one produces, including around corners. Foliage absorbs and/or diffuses sound, while sound tends to bounce off of/echo from man-made structures and bare tree trunks or rock, again including around corners. Likewise, in a room with carpets, curtains and cushioned, cloth-covered furniture, like a bedroom or living room, these objects absorb sound, whereas in indoor areas without such furnishings or with primarily smooth, bare, hard surfaces, like a stairwell or bathroom, echoes are more likely. But we now finally turn to the various types of audial target indicators themselves, the judicious use, masking, elimination or reduction of which being known as “noise discipline.” We first consider speech.

–Speaking: While the sounds of one’s movements may be overlooked or mistaken for sounds caused by animals or the wind, the sound of human speech is much more distinctive and compromising. Soft speech can be heard from ca. 300m (1000 ft) to as far as 1km (0.6 miles) away. Thus, if operating in a group, it is imperative to have prearranged signals with which to communicate in order to eliminate or at least reduce the need for speech, such as hand-and-arm signals or insect mimicry.

–Breathing: At rather close ranges, fast and heavy breathing can audially give away one’s location, as can coughing, sneezing or gasping. These can result from poor physical fitness or health, physical exertion while evading and poor mental discipline. Thus, it is imperative to hone one’s physical fitness as well as the ability to control one’s mind and breath, noting that these are all in fact interconnected. Just as good physical health can help in avoiding hyperventilation as well as reducing stress and the need to cough or sneeze, being certain to breath continuously while moving or hiding can help one to remain calm and mentally in control, thus reducing the likelihood of compromising gasps or exclamations. In the classical 17th-century ninjutsu manual entitled the Bansenshukai, a notable amount of attention is paid to breath control and the psychology of hiding. For instance, the reader is instructed to cover one’s mouth with one’s sleeve while hiding and to mentally recite the mantra of the warrior goddess Marishi Ten, who is also known for granting invisibility.

While on the topic of breathing, although this actually pertains to a visual indicator, it should be noted that breath can produce steam which can be seen in cold weather. To reduce this risk, it is advisable to exhale through the nose only as well as to cover one’s nose and mouth if occupying a static position.

–Sounds of equipment: The equipment that one may be carrying or using can produce unwanted and compromising noises. One can quickly identify any rattling gear and jingling keys, coins or other items by simply jumping up and down while listening to whatever sounds are produced. Once identified, these sounds can be eliminated or muffled by taping the offending items or by repositioning them to more secure positions in one’s load.

On another note, mobile phone ringtones or notification sounds can arrive at the least opportune moments, as anyone who has forgotten to silence their phone before a meeting and then received a call or a series or messages can surely attest to. If stealth has become a serious concern, silencing one’s mobile phone must be among one’s first actions. It is also of course important to be familiar with any other equipment you may be using and to know what sounds they may produce and how. Unexpected noises are truly unwelcome surprises while trying to evade a pursuer. Lastly, on sounds produced by equipment and for a general point of reference concerning vehicles, a running truck engine can be heard from 0.5 to 1km (0.3 to 0.6 miles) away.

–Movement (as it pertains to audial detection): Moving through and interacting with one’s environment inevitably produces noise that could compromise one’s location. That said, however, in accordance with the principle of proportionality, it is imperative to keep attempts to move silently proportionate to the likelihood of detection, especially in light of the enemy’s assessed distance from one’s location. For instance, a moving infantry unit can be heard at 300-600m away. Thus, if a group, let alone an individual, is 600m or more from the known or suspected location of their pursuers, then it makes sense to focus more on things like moving quickly to the nearest sanctuary over avoiding making the slightest noise, which the enemy would likely never hear anyway. While it could be detrimental to tromp rapidly through dry vegetation and break brush with reckless abandon when one is avoiding detection from a foe in close proximity, if that same adversary is more than 600m away, then this may be exactly what is called for to elude them and reach a safe place.

An overview of individual movement techniques; which are designed to reduce the risk of both visual and audial detection, balancing these two considerations as the situation demands; has already been provided in another article. On top of basic movement techniques; besides stealth methods of crawling, squatting movement, walking and running; there are other things that we do that could produce compromising noises, such as opening doors and moving objects. An awareness of this risk and cautious performance of such actions can help to prevent unwanted and compromising noise resulting from, for instance, surfaces rubbing against one another, hard objects colliding and mechanical or electronic functions.

If within earshot of a pursuer, it is obviously unwise to allow objects to drag on the ground or to haphazardly brush against or bump into things, or to simply drop items, deliberately or accidentally. But there are further precautions that can be taken. Instead of setting a hard object directly onto a hard surface, one can move the object to the surface, touching that surface first with one’s hand, such as with the pinky or the meaty part of the palm, and then gently and cautiously setting it down. If closing or opening a door, one can place a hand on the door frame and the other hand on the doorknob/handle, turn it and then gently close or open as necessary. This increases control and responsivity, such as in the case of a creaking door, and reduces noise that could be caused by hitting the door against the door frame or simply allowing the latch to click open or closed. With regard to closing doors, one must also assess whether this is actually even necessary. It may be better to simply leave it open or only slightly cracked and continue with one’s evasion. Furthermore, in limited visibility such as darkness, one must proceed more slowly and cautiously to avoid not only producing unwanted noise but also to prevent injury. In summary, however, a bit of foresight, attention to detail and caution can go a long way toward avoiding creating compromising noise.

Olfactory Target Indicators:

After sight and sound, smell is the third most likely way that one might be detected. While we have touched on topics like the speeds of sound and light and how far these can travel, acknowledging that these too are quite dependent upon environmental variables, smell is much more difficult to quantify in such ways and is very largely dependent on environmental factors along with the nature of the source of a given smell. Nevertheless, generally speaking, the maximum distance at which an observer can smell oneself is substantially closer than the maximum distances for visual or audial detection.

For some idea, we consider a statement from a hunting blog: “Under normal conditions, a deer can smell a human that is not making any attempt to hide its odor at least 1/4 mile [400 meters] away. If the scenting conditions are perfect (humid with a light breeze), it can even be farther.”[4] Taking into consideration that deer have a more acute sense of smell than even dogs and exponentially greater than humans, this makes clear that with regard to human detection capacity, vision and then hearing have much greater ranges. This is why olfactory indicators come in a distant third, after visual and audial indicators, in terms of priority here.

Put simply, smell is the perception of microscopic molecules emanating from an object. Obviously then, things between oneself and potential observers, such as terrain, vegetation and man-made structures (also used to obscure visual and audial indicators), can to a degree act as obstacles to these molecules, though they can still move around them. Hence, one could be completely concealed visually and entirely silent, but nevertheless be smelled at close ranges, which again underscores how achieving and maintaining distance from a pursuer is paramount

Considering further how smell relates to one’s environment, arid conditions are less favorable to an enemy’s ability to smell, whereas humid conditions are more so. That said, however, warmer temperatures facilitate the vaporization of liquids and solids into gases, thus facilitating smell, while cooler temperatures have the opposite effect. Of further note, enclosed spaces can trap scents, whereas open or well-ventilated spaces allow scent to dissipate.

Moreover, and of particular significance, wind (even the slightest breeze) can blow scent further distances and toward an observer that one is positioned upwind from, or it can blow the scent away from an observer that one is positioned downwind from. Thus, it is obviously preferrable to maintain an awareness of wind direction along with the enemy’s likely or known location and to remain downwind of them. To roughly determine wind direction, one can wet one’s finger or thumb all the way around its circumference and stick it in the air, feeling for whichever side feels the coolest to determine where the wind is blowing from. Another method is to toss grass, leaves or dust into the air and then watch which direction they drift toward.

Thus far, we can discern three basic general strategies, regardless of humidity or temperature, for counteracting olfactory target indicators (the first two also applying to visual and audial indicators): 1- place barriers (terrain, vegetation and man-made structures) between oneself and the enemy, 2- achieve and maintain distance from pursuers and 3- stay downwind from them. All three of these apply to the two subcategories of olfactory target indicators, which we divide into smell of oneself and smell of one’s equipment and activities, turning first to the former.

–Smell of Oneself: Sources of scent that can be distinctive on one’s person include hygiene products, insect repellent, sunscreen, laundry detergent, aromatic foods (especially if foreign to the region in which one is operating) whether being prepared and eaten or afterwards, candy, breath mints, chewing gum, alcohol and tobacco products (including smokeless tobacco like chew or snuff). One approach is to avoid consuming the full range of the kinds of products described here. For some products, namely alcohol and tobacco, this is advisable for multiple reasons, such as to avoid clouding the mind with alcohol or to prevent tobacco use from adversely affecting one’s cardiovascular fitness and risk of cancer, not to mention the problem of nicotine withdrawal acting as an unnecessarily added stressor and distraction during an evasion situation. On the other factors, it is often recounted that during the Vietnam Conflict, American snipers would reside separately from their countrymen, avoiding their hygiene products and exclusively consuming the food eaten by locals in order to reduce the chances of olfactory detection in the field.

Yet in accordance with the principle of proportionality, aside from some lifestyle choices like avoiding alcohol and tobacco, for the average person, it would be unnecessarily extreme to eliminate all of the above sources of smell from one’s life. Alongside implementing the strategies of achieving distance, using barriers and remaining downwind, one could further mitigate the risk of olfactory detection by avoiding the use of sources of strong scent while actually engaged in evading. Moreover, if the situation permits, one can wash/wipe off any areas where aromatic products have been applied, especially, for instance, perfume or cologne. A further measure could be using smoke, particularly from fragrant plants like pine, to help mask one’s smell, allowing it to waft over oneself and clothing. Yet the use of fire, and burning aromatic plants in particular, is inadvisable in almost all situations in which stealth is a necessity, which brings us to the next category of olfactory target indicators, the scents produced from one’s equipment and activities.

–Smell of One’s Equipment and Activities The equipment one is using as well as the activities one is engaged in can also emit compromising scents. Fuel, anti-freeze, lubricants and other fluids required for the operation of some equipment, like vehicles and generators, can produce noticeable and distinctive smells. In addition to the strategies of maximizing distance and obstacles along with remaining downwind, proper equipment maintenance, including preventing and repairing leaks, is key here to avoid exacerbating this unavoidable problem. Good maintenance can also reduce how pronounced and compromising exhaust fumes may be, not to mention the sounds produced by their operation.

On another note, fires and cooking stoves can also release highly compromising scents, as well as visual indicators through smoke and light. Again, it is thus imperative, when stealth is a priority, to not build fires or use cooking stoves unless absolutely and immediately necessary for survival. It is preferrable to eat food that does not need to be cooked and to rely more on proper thermoregulation strategies, such as the proper use and selection of clothing and shelter as well as preventing avoidable heat transfer, such as through conduction, convection and evaporation.

Lastly, and related to one’s activities, the scent one leaves behind as one moves through an area can also be detected by tracking dogs after one has already departed. While such tracking capability is characteristic of more sophisticated threats and is thus of less concern to us here, it does bring us to the next category to consider, that is recognition factors which are indirect.

Indirect Target Indicators:

Aside from the above direct target indicators, which involve observers perceiving oneself, one’s equipment or position directly, there is also the possibility that such observers could be alerted to one’s approximate whereabouts through indirect means, such as traces that one leaves behind or forewarnings of one’s presence. We first begin with the latter.

–Disturbed animals/insects: Examples of this category of indirect target indicators include barking dogs, spooked cattle, startled birds flying away and the sudden silence of insects. While the last factor of insects might be more difficult to avoid, the other situations can often be foreseen, avoided and prevented, such as if approaching a farm, residential area or a body of water where water fowl may be gathered. The same stealth movement techniques along with countermeasures against visual, audial and olfactory detection that one may use against humans can also be applied to animals, though their effectiveness is of course not as great against animals with keener senses of sight, hearing or smell. Again, remaining downwind in relation to such exposure hazards is important for both sound and smell. Avoiding tracking dogs is an entire field unto itself, but one which is unlikely to be a concern for law-abiding persons using stealth as a means of self-protection. It is thus not addressed here.

–Local human informants: Generally speaking, third party persons (those other than oneself and companions or the adversary) should be seen more as potential sources of aid, and sought out, rather than as a risk factor for exposure to be avoided. Nevertheless, they may knowingly or unknowingly provide the threat with compromising information, such as one’s last known location, direction of movement, numbers, equipment, state of health, etc. One should thus assess whether locals could be a source of aid and should be contacted or not and are to be avoided. The present author, however, has a rather optimistic perspective and would argue that unless in a war zone or an area where the populace may be colluding with or is being coerced by organized crime or an oppressive hostile government, if there are third party persons, they should be contacted and asked for aid. Even in such extreme circumstances, a decision to contact, informed by a knowledge of the likely loyalties and sympathies of such persons, may be one’s best option. At the very least, they may be able to hide one for a short while. If there is a risk that such persons may later provide information to one’s pursuers, knowingly or unknowingly, one can be cautious with how much and what kinds of information one reveals to them. If the threat you are eluding could also be a danger to third party individuals, there is also the moral imperative of needing to warn them, which requires some degree of contact, or even to facilitate their escape as well. But to reiterate, and in closing, in the majority of situations (unless you are a criminal, a spy or a soldier behind enemy lines), third-party human beings should be contacted and seen more as a potential source of aid than as a risk factor for exposure.

–Tracking signs To avoid being tracked by signs of your presence that you may have left behind, try to minimize signs like footprints, disturbed soil, rocks and vegetation as well as garbage (the latter being known as practicing good “litter discipline”) and human waste (which can be buried in catholes). Strive not to leave any trace of your presence, leaving the area just as you found it. This is not only an important evasive measure, but it is also good environmental stewardship. Avoid walking on terrain like mud that leaves obvious footprints and try not to leave a trail of broken brush and disturbed foliage in your wake.

If one intends to hide behind a wall of foliage, it is unwise to simply break through the wall and attempt to hide at that location, since the disturbed vegetation can draw an observer’s attention. If one must break through the layer of vegetation to get behind it, it is better to break through at an already thinner and/or less notable place or somewhere that will be out view from the perspective of the enemy’s suspected or known position. Even better is to leave the foliage entirely undisturbed by going around (or over, such as jumping over the first couple of feet of tall grass that one intends to lie down in).

Aside from these basic guidelines, as alluded to already, counter-tracking is another entire field unto itself. It involves taking special measures to prevent leaving signs behind for a tracker to pick up on and follow, removing signs that have been made and incorporating deceptive maneuvers into one’s evasion plan that leave misleading signs behind to throw off human trackers as well as tracking dogs from one’s true trail. Unless in areas like snow-, sand- or mud-covered terrain where tracks may be quite apparent, tracking abilities are characteristic of more sophisticated threats. Thus counter-tracking is seen as a more advanced skill that is not addressed here for the average law-abiding citizen.

Having discussed the three approaches of camouflage, concealment and deception in the first article of this series, and in this article the various target indicators or recognition factors, whether visual, audial or olfactory, the next article delves into several practical exercises which help to train one’s ability to make use of the above approaches to reduce or eliminate target indicators to prevent detection from hostile elements.

Bibliography

Baden-Powell, Robert. Scouting for Boys: A Handbook for Instruction in Good Citizenship. London: C. Arthur Pearson Ltd., 1915.

Birkby, Robert C. The Boy Scout Handbook, 10th Ed. Irving, TX: Boy Scouts of America, 1990.

Davidson, Phillip L. SWAT (Special Weapons and Tactics). Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1979.

Dermody, Matthew. Appear to Vanish: Stealth Concepts for Effective Camouflage and Concealment (Lexington, KY: Hidden Success Tactical, 2018).

Dolmatov, A.I. KGB Alpha Team Training Manual: How the Soviets Trained for Personal Combat, Assassination, and Subversion. Boulder, CO: Paladin Press, 1993.

Itoh, Gingetsu. Gendaijin no Ninjutsu. Trans. Eric Shahan. Charleston: CreateSpace, 2014.

Itoh, Gingetsu. Ninjutsu no Gokui. Trans. Eric Shahan. Charleston: CreateSpace, 2014.

Murray, Malcolm G. “Aimable Air/Sea Rescue Signal Mirrors.” TBP.org, 2004, www.tbp.org/pubs/Features/F04Murray.pdf.

“Q & A: Speed of Sound and Light.” Q & A: Speed of Sound and Light | Department of Physics | University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, accessed April 23, 2021, van.physics.illinois.edu/qa/listing.php?id=2076.

ReWildUniversity, “How to Escape from Pursuers in the Woods (An Evasion Skill-Building Game),” accessed April 23, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HfSij50oJ14.

Simoni︠a︡n, Raĭr Georgievich., and Sergeĭ Vladimirovich Grishin. Tactical Reconnaissance: A Soviet View. Washington, DC: US GPO, 1990.

U.S. Department of the Army. Camouflage, Concealment, and Decoys. Field Manual 20-3. Washington, DC: Headquarters, Dept. of the Army, 1999.

U.S. Department of the Army. Infantry Platoon and Squad. ATP 3-21.8. Washington, DC: Headquarters, Dept. of the Army, 2016.

U.S. Department of the Army. Sniper Training. Field Manual 23-10. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Army, 1994.

U.S. Department of the Army. Survival. Field Manual 21-76. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Army, 1992.

U.S. Department of the Army. The Warrior Ethos and Soldier Combat Skills. Field Manual 3-21.75. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Army, 2008.

U.S. Department of the Navy. U.S. Navy SEAL Sniper Training Program. New York: Skyhorse, 2011.

U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff. Survival, Evasion, and Recovery: Multiservice Procedures for Survival, Evasion, and Recovery. Washington, DC: U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2010.

U.S. Marine Corps. Introduction to Evasion and Resistance to Capture. MCI 0327. Washington, DC: Marine Barracks, 2008.

Winke, Bill. “Can Deer Tell How Far Away a Source of an Odor Is?.” BowHuntingMag.com. Accessed April 11, 2021, https://www.bowhuntingmag.com/editorial/can-deer-tell-how-far-away-a-source-of-an-odor-is/309382#:~:text=%2D%2D%20Chad%20Carl%2C%20Washington%2C%20Pa,it%20can%20even%20be%20farther.

[1] “Q & A: Speed of Sound and Light.” Q & A: Speed of Sound and Light | Department of Physics | University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, accessed April 23, 2021, van.physics.illinois.edu/qa/listing.php?id=2076.

[2] Malcolm G. Murray, “Aimable Air/Sea Rescue Signal Mirrors,” TBP.org, 2004, www.tbp.org/pubs/Features/F04Murray.pdf.

[3] US Department of the Army, Infantry Platoon and Squad, ATP 3-21.8 (Washington, DC: Headquarters, Dept. of the Army, 2016), 2-22.

[4] Bill Winke, “Can Deer Tell How Far Away a Source of an Odor Is?,” BowHuntingMag.com, accessed April 11, 2021, https://www.bowhuntingmag.com/editorial/can-deer-tell-how-far-away-a-source-of-an-odor-is/309382#:~:text=%2D%2D%20Chad%20Carl%2C%20Washington%2C%20Pa,it%20can%20even%20be%20farther.