As noted in the earlier article on weather analysis, when planning for any kind of undertaking, but especially for escape and evasion, it is essential to consider how weather, terrain and human factors will impact oneself, the members of one’s group, equipment used and the ability to accomplish the intended objective. It is also of course crucial to consider how these factors may impact any pursuers or adversaries. Such analysis involves figuring out how to harmonize and fit in with the way the universe works, how it operates, or what has been called the scheme of totality or the law of heaven.

Chiton Jūppō (地遁十法, “10 Earth Methods of Escaping”)

In the article on weather analysis, we pointed to the system of thirty methods for escape and evasion that have been attributed to the Japanese ninja, namely, the tenchijin santon no hō (天地人三遁の法, “heaven, earth, man-three methods of escaping”). We also enumerated the first set of ten, that is the tenton juppō (天遁十法, “ten heaven methods of escaping/disappearing”). Here, it seems prudent to refer to the second ten-fold set, the chiton jūppō (地遁十法, “10 earth methods of escaping), which includes mokuton (木遁, “wood escape”), sōton (草遁, “grass escape”), katon (火遁, “fire escape”), enton (煙遁, “smoke escape”), doton (土遁, “earth escape”), okuton (屋遁, “house escape”), kinton (金遁, “metal escape”), setton (石遁, “stone escape”), suiton (水遁, “water escape”) and yuton (湯遁, “hot water escape”).

Obviously, these “ten earth methods of escaping” cover a large range of topics, from operating in urban terrain to incendiary warfare and amphibious or naval operations. Here, however, let’s look to what is perhaps the most central and important of these ten earth methods, and in fact, of all the thirty methods: doton (土遁, “earth escape”). For some idea of the significance attributed to this method, Tanemura Shoto states that “from Doton comes all other techniques.”[1] Similarly, Fujita Seiko emphasizes its importance by saying that it is the method that is most likely to keep one safe.[2]

Moreover, Itoh Gingetsu provides a six-fold typology of the applications of doton. These include taking advantage of the shape of the terrain for concealment (using dead space), blending with its color, relying on the consistency of the soil to serve as a distractor or blinding agent by throwing it at one’s opponent, taking advantage of steep ground and the resulting power of gravity along with relying on difficult terrain with poor trafficability to obstruct pursuers. The sixth and final category of doton he provides is a catchall for everything not included in the tenchijin santon no ho, since everything in our human experience has some relation to the earth to some degree or another. Hence, he highlights not only the centrality of doton, but also how the ninja did not limit themselves with regard to the means they worked with to achieve their ends.[3]

Contemporary Military Terrain Analysis

The above-described systematic approach to capitalizing on the advantages provided by terrain has corollaries with the terrain analysis performed by modern militaries. Such can offer valuable insights for escape and evasion as an approach to self-defense.

To begin with, important for terrain analysis is being able to identify terrain features, both directly in person and on a map by reading contour lines. This facilitates planning and communication as well as orientation and land navigation by terrain association.

The US Army divides terrain features into five major, three minor and two supplementary or man-made features. The five major terrain features are hill, valley, ridge, saddle and depression. The three minor terrain features include draw, spur and cliff, while the two man-made features are cut and fill.[4] In addition to these, when analyzing terrain, one must also take into account bodies of water, significant vegetation and man-made structures like urban areas, buildings and fences.

But terrain analysis is not simply identifying the different terrain features along your route, at your objective and in your area of operation. It must go a step further by analyzing how those features may facilitate or hinder the accomplishment of your aims, as well as those of potential pursuers or adversaries, along with how weather factors interact with terrain features.

So, for some examples, hilltops provide good observation, ridges offer not only good observation but also ease of travel, valleys and draws can contain water, saddles can provide protection from wind for campsites and steep terrain like cliffs and mountains or rivers and fences act as obstacles to movement. Perhaps the best-known terrain advantage is occupying higher ground than one’s adversary. This is clearly advantageous for the use of firearms and other projectile weapons, but as just noted, it also facilitates observation (as well as signaling for help), not to mention how, as just alluded to, gravity itself acts as an obstacle and inhibiting factor when attempting to ascend steep terrain, while it can substantially ease descent.

To this analytical end and analogous to the five military aspects of weather, there are also five aspects of terrain which bear special significance. These are summarized in the acronym OCOKA (Observation, Camouflage, Concealment and Cover, Obstacles, Key Terrain, Avenues of Approach), covered here in a slightly modified order (OCOAK) for clarity.[5] OCOKA is a mnemonic device for recalling the main points to consider when conducting terrain analysis for military operations. Yet these same points can also be applied to the terrain analysis conducted by the average individual practicing stealth as a hobby or as a means of self-protection.

Before proceeding to discuss each aspect of OCOKA individually, it is worth noting that there is substantial interplay between the different elements thereof. First, there are two pairs within this set of five which are interrelated, or even complementary, in much the same way as the Taoist concepts of yin 陰 and yang 陽 (or in and yō in Japanese). These two pairs are 1.) observation vis-à-vis camouflage, cover and concealment (CCC), along with 2.) obstacles vis-à-vis avenues of approach. Second, the fifth element of key terrain, much like the notion of kū or sora (空, “heaven,” “sky” or “void”), both combines and transcends the other four elements. We will go into further detail on these themes below.

But whether understanding one’s general area of operations, selecting a quite temporary location for hiding or for an overnight patrol base, or selecting a route to travel along, the following are important terrain factors to consider:

O – Observation: Choose locations, areas and routes that allow for good observation of one’s surroundings, particularly avenues of approach, key terrain and, if near one’s ultimate destination, the objective itself. Here we discuss this in terms of one’s own ability to observe, but an important aspect of terrain analysis is also considering the vantage points of others, whether enemies or potential sources of aid to which one can signal. The same concepts apply when analyzing from these other perspectives.

As already alluded to above, this first OCOKA factor of observation is inextricably linked with, while seemingly diametrically opposed to, the second OCOKA factor: CCC. For good observation, one must have unobstructed line of sight (LOS) for oneself, but while also being camouflaged, covered and concealed from enemy observation and fire. Thus, a balance must be achieved to maintain both good observation as well as good CCC.

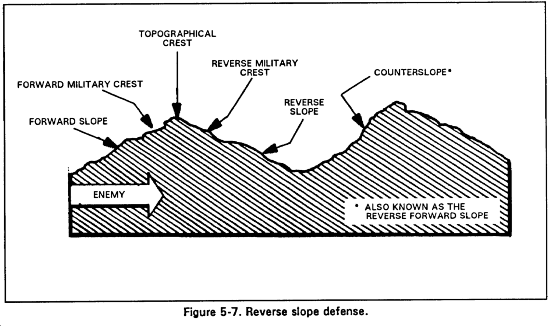

For a significant example, standing on the topographical crest of a hill generally allows for excellent observation in all directions, though it may not offer the best opportunities for CCC. The military crest, however, provides good observation in around 180 degrees, depending on the terrain and any obstructions to a clear LOS, but substantially better CCC, reducing the risk of exposure from silhouetting, increasing opportunities for blending and giving greater cover (if situated on the reverse slope, discussed below). This seems like a reasonable compromise. Hence, moving along and/or taking up positions on the military crest is especially conducive to stealth.

It is important to distinguish between two types of military crest, namely, the reverse and forward military crests. The reverse military crest is on the reverse slope, the side away from an enemy or observer. It allows for superior concealment, though observation of the enemy is greatly limited. The forward military crest, however, is on the forward slope, that which faces the enemy/observer. In contrast, it provides better observation of adversaries or pursuers, but fewer possibilities for concealment provided by the terrain itself, though this can be compensated for by relying more on camouflage and blending as well as using available vegetation or man-made structures for concealment.

As already noted in the article on target indicators, and for another example of balancing observation and CCC, when observing from behind concealment, it is best to look under, around or through, rather than over, so as to avoid silhouetting. Also, be aware of your background for the same purpose (to avoid silhouetting) as well as to facilitate camouflage by blending with that background. But now we turn more fully to the topic of CCC itself.

C – Camouflage, Concealment and Cover: Select areas, locations and/or routes that offer sufficient opportunities to blend in and/or conceal yourself, and if necessary, protect from bullets. CCC has already been addressed at length in the series of articles entitled, “Fundamentals of Stealth for Self-Protection,” especially “Introduction and Three Approaches to Hiding” and “Target Indicators.” The full contents of that series will not be recounted here. Instead, we will make a few notes pertaining specifically to terrain and its relationship to CCC.

When stealth is imperative, priority should be accorded above all to remaining within 1.) the dead space afforded by the terrain (including being behind vegetation and man-made structures), followed by 2.) staying within shadows and lastly, 3.) striving to blend with the environment with respect to color, contrast and texture. Of course, it is not so simple as one approach being selected instead of the other two, as these must all be used in combination with respect to different observer vantage points. In fact, all three may well, and if possible should, be used simultaneously to hinder detection from any single vantage point. For instance, an ideal combination would be remaining partially concealed behind a wall of foliage, within the shadows afforded by such vegetation and while approximating the environment in terms of color, contrast and texture with sources of light and shine eliminated or subdued. Moreover, when moving, one must use whichever of these (dead space, shadows and blending), or combination thereof, is available at any given point along one’s route.

Dead Space

To elaborate, in terms of avoiding visual detection, by far the most effective and certain means is by operating within dead space. Dead space is an area that cannot be observed from a particular position because of barriers or obstructions to LoS/observation like terrain, man-made structures and dense layers of vegetation. Thus, remaining within dead space by being on the reverse slope as well as moving or positioning oneself in ditches and depressions or behind buildings or layers of significant vegetation obstructs the observer’s vision, thereby concealing oneself.

Such concealment will of course hinder one’s own observation, however, and cannot be relied upon exclusively if one is to maintain appropriate awareness of one’s surroundings. Here, the above-described precautionary measures for observing from behind concealment come into play, namely, looking through, under or around rather than over (unless there is a suitable background and/or foreground obstructions to facilitate blending).

We might also speak of “partial dead space,” where one may not be entirely concealed, such as behind a layer of relatively dense foliage, but the extent of concealment is so great that an observer would have to investigate very thoroughly to discover one’s presence. Such partial concealment has the benefit of allowing for observation by peering through its gaps.

Shadows

As already discussed and demonstrated in the article on target indicators, shadows significantly facilitate camouflage and should especially be used in situations when it is impractical or impossible to remain completely, or even just partially, concealed within dead space. When static, one should take up positions within shadows and when moving, one should stay within shadows as best as possible, or follow the “shadow trails,” so to speak. This applies as much to when operating in daylight as it does to being in darkness.

There are a number of factors that make shadows so effective and useful for camouflage. These include how the human eye does not perceive color in darkness, how differences in contrast and texture are also muted to varying degrees and how potentially reflective surfaces are exposed to fewer sources of light to reflect. It is particularly efficacious to remain within the deepest, darkest part of a shadow (the umbra) as opposed to its lighter periphery (the penumbra).

Due to the abovementioned factors, shadows can instantly facilitate one’s efforts at blending, thus allowing one to seemingly disappear immediately and without resorting to additional measures. Thus, shadows offer the next best option after dead space (and partial dead space). They also offer the added benefit of being able to observe, something that is also true of blending, the topic to which we now turn.

Blending

While, as just noted, shadows significantly facilitate blending, here we are referring specifically to blending with the environment in terms of color, contrast and texture, not to mention reducing or eliminating sources of shine and light. Hence, this discussion applies whether or not one has made use of shadows to facilitate such blending.

One may be able to blend with one’s surroundings by simply taking up a position in or moving through an area that already roughly approximates the color, contrast and texture of one’s person, clothing and equipment as is and without modification. For instance, it would be unwise to position oneself against a light-colored background while wearing dark clothing, or a dark-colored background with light clothing, but if in front of a light background with light clothing or a dark background with dark clothing, one may not stand out quite so much as in the former situations.

It is of course also possible to take extra measures, such as wearing camouflage clothing or a ghillie suit, applying natural or artificial materials for camouflage, dying one’s clothing, covering and/or painting exposed skin and/or hair that might give one away, etc. Yet such measures require forethought and/or time to execute. It is not only unrealistic, but also neurotic to strive to be perpetually prepared to blend with one’s surroundings. Moreover, the time to implement such measures may not be available. It is thus hoped that the reason for emphasizing the use of dead space and then shadows over attempting to blend now makes some sense to the reader.

Final Notes on Terrain and CCC/Stealth

On a related topic, while not usually considered with respect to conventional military terrain analysis, for the purposes of stealth as a means of self-protection, the acoustics of the terrain may also be important to consider. Thus, we may factor in whether sound will be absorbed, such as by thick vegetation or soil, or whether it will echo, bouncing off of surfaces like rock, concrete, metal or glass.

As with all of the OCOKA considerations, in addition to analyzing terrain in terms of the opportunities for CCC that it can provide oneself, it should also be analyzed with respect to the opportunities for CCC that it can afford to enemies. Identified sources of enemy CCC, such as dead space, shadows and significant vegetation should be noted and treated with a level of caution that is proportionate to the assessed level of risk.

When planning routes, it is important to identify danger areas. These are places where one may be exposed to enemy observation and/or fire due to the absence of sufficient CCC. We can speak of small or large open danger areas, like a clearing in a forest, a field, a lawn or an open courtyard, as well as of linear danger areas, like trails, roads, streets and streams or rivers. Wherever possible, bypass danger areas or use the appropriate individual and collective movement techniques to traverse them, which brings us to another point.

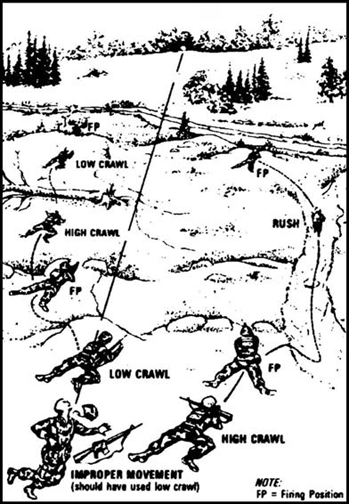

Terrain characteristics providing dead space, shadows or opportunities for blending, or the lack thereof, not only dictate the locations and routes in which one is operating, but they also determine the movement techniques used to traverse through those areas and routes. This is true at both the individual and the collective level. For further details, see the articles entitled “Individual Stealth Movement” and “Group Stealth Movement.” The below image, taken from a US Army field manual, illustrates how the availability of CCC provided by the terrain dictates not only route selection, but also the individual movement techniques used to traverse that route.

Similarly, terrain features, in conjunction with the assessed or known distance from potential adversaries and objective areas, help one to decide when to transition between simple movement, much as one would perform while hiking for leisure, and more cautious and stealthy tactical maneuvering. This is important because the latter form of movement and level of awareness is impractical to maintain for extended periods or over long distances. If the risk of detection is low for a particular portion of one’s route, then the mental and physical energy required for strictly executed tactical movement might be better spent in other ways or preserved for later use, such as in surmounting obstacles, the next topic of discussion.

Camouflaging and Concealing Intention

But before leaving the topic of CCC altogether, beyond concealing one’s actual physical form, it is also possible to hide one’s intentions and/or identity while being physically visible. This is illustrated in the difference between modern infantry carrying out their mission under actual physical CCC and spies pursuing their ends while physically visible but with their identities and intentions concealed, camouflaged or disguised. Such a distinction is found in the divisions of innin (陰忍, “shadow method”) and yōnin (陽忍, “sunlight method”) as found in the classic text on ninjutsu known as the Bansenshukai (1676). With the latter “sunlight” approach, one relies not on opportunities the terrain affords in terms of dead space, shadows and blending to hide one’s physical form, but on what has been called cover for status and cover for action that the environment may provide. Such hiding in plain sight could be used by oneself for “going gray” to avoid be singled out as a target or by adversaries to conceal their intentions while conducting surveillance or carrying out an attack. This topic is only mentioned here, but will be discussed further in other articles.

O – Obstacles: Identify obstacles and how they could affect your own mobility as well as that of any enemy or rescue personnel. Obstacles may simply slow down one’s movement or it may be hindered altogether. Examples of obstacles include bodies of water, dense vegetation, steep terrain, marshland, man-made structures like fences, walls and buildings or crowded city streets.

Bodies of water, if not circumvented, must be crossed by wading or swimming across or using special equipment like watercraft or a rope. Dense vegetation, marshland and steep terrain all significantly slow movement. The latter may be impossible without special equipment like climbing/mountaineering gear and the necessary knowledge and proficiency in using them. Likewise, such obstacles may be completely untraversable in a land vehicle, which obviously cannot drive through densely arrayed trees or up a cliff, and which could become mired in wetlands. Fences may be scaled, dug under or cut through, but this too slows one down as well as increases the risk of discovery, whether during the process of breaching or after its completion. Moreover, obstacles emplaced by human beings may very well be under observation.

When conducting terrain analysis while planning one’s route, it is thus imperative to consider whether one (and if applicable, the members of one’s group) has the necessary equipment (if any is required), training, physical ability and emotional resolve or willpower necessary to overcome a given obstacle. One must also consider the risk of exposure while crossing a given obstacle.

Hence, after obstacles have been identified, for each one, ask whether or not there are reasonable and expedient possibilities for circumventing these obstacles. If not, then the next question is whether or not any special equipment and/or skills are needed to overcome the identified obstacles and whether one has these or suitably expedient substitutes. It is also necessary to assess whether or not one has the physical ability to surmount a given obstacle, whether in terms of one’s level of physical fitness, degree of restedness or other limitations such as height, weight or a medical handicap. Also take stock of one’s level of morale and motivation to determine whether or not one has the willpower, a finite resource, to follow through in crossing the obstacle to completion.

The same considerations should be taken into account with regard to all members of one’s group. Also take into account whether the degree of exposure involved in crossing the obstacle entails an acceptable level of risk. If the obstacle is ultimately determined to be insurmountable or impractical, then it is of course necessary to resort to circumventing it despite the inconveniences and delays involved. This same process is repeated for all obstacles along one’s selected primary and alternative routes.

But beyond avoiding obstacles or determining the feasibility of negotiating them, it is also necessary to consider how obstacles could prevent others from finding and/or reaching you. In particular, we are referring here to any hostile elements as well as to any potential sources of aid, like rescue crews.

Obstacles and Enemy Personnel

First, pertaining to adversaries, when planning a route and also when choosing a static location, such as for a campsite, one may deliberately select difficult terrain to do the unexpected, to camp in a site that no pursuer would suspect or to move along a route or approach from a direction that no one would conceive of (like the example of Hannibal crossing the Alps mentioned below).

In any case, whether you are static or moving, it is advantageous to place obstacles between oneself and one’s enemies to prevent or at least to delay their attempts to reach you. Using the well-known example of higher ground as an advantage of terrain, if the enemy has to climb up a steep slope to reach you, then gravity will be working against their efforts to do so and will substantially slow their advance, hopefully allowing you the time necessary to escape. Of course, other obstacles, like dense vegetation or swampy terrain, can be used in the same way. In static positions, such obstacles may also act as early warning systems, since, for instance, the enemy breaking brush or sloshing through mud or water to reach you may certainly alert you to their presence well in advance.

Using obstacles to hinder an enemy’s approach can also help to focus one’s own security efforts by allowing one to concentrate their attention on the most likely enemy avenues of approach. Of course, as famously demonstrated by Hannibal’s crossing of the Alps with elephants in 218 BC, the presence of an obstacle does not guarantee that an enemy will not approach from that direction. Thus, while one may focus their attention on the most likely avenues of approach, less likely ones cannot be ignored.

It is also important to consider that a particular route may be trafficable to someone on foot but intrafficable for vehicles. If one’s pursuers are in vehicles, choosing a route through a dense forest or a crowded pedestrian area basically forces them to dismount and continue their pursuit on foot, thus at least negating any advantage provided by their being in vehicles.

On a final note regarding the use of obstacles to inhibit the approach of enemies, it is important to have identified avenues of egress so that these same protective obstacles do not prevent one’s own escape should the need arise.

Obstacles and Rescue Personnel

In contrast to using obstacles to hinder the approach of adversaries, in the case of needing to be rescued, it is of course preferred to have as few obstacles as possible between oneself and potential sources of aid. Being located near or in an inhabited area and on a high-speed avenue of approach like a road is highly preferred over being off in the hinterlands somewhere, away from all civilization. Moreover, while hopefully no average citizens reading this will ever have to evade an adversary that possesses aviation assets, aerial avenues of approach and whether there is sufficient clearance for a rescue helicopter to land safely are worth considering. Rescues without landing are certainly possible, but they are not ideal.

A – Avenues of Approach: Identify clear routes and natural lines of drift (NLDs, namely, the routes most logical to be taken when moving from one point to another due to offering the least resistance and obstacles), including especially high-speed avenues of approach like trails and roads, and consider how these could be used by oneself for general movement, escape and evasion as well as by others, like one’s adversaries or rescue teams, in reaching one’s location or decisive terrain (described below).

Avenues of approach need not necessarily be straight lines, as they may meander around obstacles and changing topography. Moreover, in terms of size, they may constitute quite broad movement corridors like an open field, miniscule foot trails or anything in between. They may be by air, sea or land, or even subterranean. They may be traversable by vehicle, foot or both. In urban settings, one must consider street design, including noting one-way streets, along with the various ways of getting in and out of any relevant buildings, as well as moving within them, such as doors, windows, fire escapes, roof access points, hallways, stairwells, etc.

Route Planning

Routes must be selected for a variety of reasons, including for the accomplishment of one’s overall mission as well as for supporting tasks like resupply, water acquisition, medical evacuation or exfiltration from a particular location, such as a bivouac site or a building. When weighing the advantages and disadvantages of identified routes for one’s own use, important factors to take into account include known or suspected locations of the enemy, distance to be travelled, requirements for fuel, food, water and rest, sources of such supplies while en route, trafficability of the terrain, speed of movement and whether or not there are significant obstacles, along with the degree of CCC and observation afforded while traversing such routes.

Also consider important landmarks or terrain features which can serve as waypoints to track one’s progress as well as to aid in navigation through terrain association. In this regard, one may choose to travel parallel to a linear terrain feature like a road, trail, river or ridgeline. This is a land navigation technique known as “handrailing.” One could also use such a linear feature as a “backstop” to know when one has gone too far. It is also possible to plan a “panic azimuth” that leads to such a linear feature to help in reorientation should one become lost. Routes may avoid obstacles by contouring around them or by boxing around them with four ninety-degree turns (RLLR or LRRL).

Channelized Terrain and Choke Points

It is important to identify “channelized terrain” and “choke points” along one’s selected routes, both because of the limitations they entail as well as because they are potential sites for an ambush. If an ambush is expected or even simply possible, the need to identify these is essential.

Channelized terrain forces one to follow a particular route, therefore making one highly predictable and thus easier for the enemy to target. Examples include bridges, overpasses, tunnels, escalators, stairways, elevators, entrances/exits, public transportation, one-way streets and streets with few possibilities to turn off or exit. In fact, anytime one is following an established road or trail, they are channelized and thus predictable and targetable.

Yet an especially important type of channelized terrain is referred to as a choke point. With respect to military strategy and planning, choke points are narrow places along an avenue of approach which an element must pass through to accomplish their objective. Because of such narrowness, choke points limit the amount of force that an element can bring to bear to the front of their formation. Hence, choke points act as a kind of equalizer between forces of different sizes, allowing smaller forces to defend against and even defeat a larger force.

Classic examples of such successful exploitation of choke points include the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC, wherein Leonidas I defended against the Persian Xerxes I’s invasion at the pass of Thermopylae, or the Battle of Agincourt in 1415 CE, when a smaller English force of largely archers were able to defeat a much larger French force of heavy cavalry mired in a muddy woodland pass.

For contemporary self-protection purposes, however, the term choke point could be used denote a channelized area along one’s route in which one must slow down or stop. Obvious examples include construction zones, traffic circles or places where one must turn against oncoming traffic, but any of the examples of channelized terrain described above could also be chokepoints.

Choke points should be identified in the planning process because they not only slow movement, but because they are also excellent ambush sites.

Static Positions and Avenues of Approach

Pertaining to static positions and avenues of approach, as a general rule of thumb for when practicing stealth, avoid taking up positions near natural lines of drift. This reduces the likelihood of an adversary stumbling upon one’s location by coincidence. Nevertheless, it is crucial to have preestablished avenues of egress from any static locations that one may occupy. It is also essential to have good observation of all potential enemy avenues of approach to one’s location.

Finally, if rescue is required at a given location, the case is the opposite from when avoiding enemy contact, since it is best to be located on or near major avenues of approach. One must consider whether potential avenues of approach for rescue personnel are feasible. If they are not, then relocation must be considered, but in light of the ability to do so, especially with regard to any injured personnel and the risk of further injury that might be caused by relocating.

K – Key Terrain: Key terrain is usually defined, in sources like FM 7-8 (Infantry Platoon and Squad) or the Ranger Handbook, as “locations or areas whose seizure, retention, or control gives a marked advantage to either combatant.” For our evasion-focused concerns, “seizure, retention, or control” shall be understood as simply occupying a particular location. The term “advantage” in this definition, however, would be largely determined by what it is one is intending to accomplish, like evasion/escape, pursuit/attack or rescue/evacuation. The respective advantages for such different objectives often relate directly to observation, CCC, obstacles and avenues of approach.

Thus, when evading/escaping or pursuing/attacking, the terrain occupied at any point in the endeavor should generally afford good CCC along with good observation, especially of avenues of approach. Moreover, one’s opponents’ movement should be restricted by obstacles while enjoying freedom of movement for oneself. For rescue/evacuation efforts, however, it is most advantageous for rescuers and those to be rescued to have clear observation of one another, as few obstacles between them as possible, and to be rapidly accessible to one another by high speed avenues of approach.

So in other words, for our purposes, key terrain is comprised of areas that are advantageous (whatever that may mean for one’s given objectives) in terms of all four of the other facets of OCOKA, namely, observation, CCC, obstacles and avenues of approach.

This composite concept is directly related to the planning process, as the location of key terrain will dictate one’s positions and selected routes, since one ought to occupy positions and use routes which meet these criteria.

Decisive Terrain

Yet there is also the issue of a specific type of key terrain known as “decisive terrain,” defined by FM 7-8 as “key terrain which seizure, retention, or control is necessary for mission accomplishment.” For us, if the objective is to reach sanctuary and acquire assistance at a safe place, like a shopping mall, hospital, public library or police station, then any such locations would not only be key terrain, but would also specifically count as decisive terrain. An identified and selected rescue site would also count as decisive terrain.

For hostile elements, decisive terrain might be surveillance locations and ambush sites. These provide them with good observation of their target, good CCC for themselves (including cover for action and status if physically visible), while also channelizing the target into the kill zone and keeping them there by way of obstacles as well as offering good avenues of ingress and egress for themselves before and after their objective is complete.

Bibliography

ArmyStudyGuide.com. “Identify Major / Minor Terrain Features.” https://www.armystudyguide.com/content/army_board_study_guide_topics/land_navigation_map_reading/identify-major-minor-terr.shtml (accessed August 31, 2021).

Itoh, Gingetsu. Gendaijin no Ninjutsu. Trans. Eric Shahan. Charleston, SC: CreateSpace, 2014.

Seiko, Fujita. Ninjutsu Kara Spy-sen E (The Secrets of Koga-ryu Ninjutsu). Trans.

Don Roley. Colorado Springs, Colorado: Freedom to Excel LLC, 2015.

Tanemura, Shoto. Ninpo Secrets: Philosophy, History and Techniques, 3rd Ed. Matsubushi, Japan: Genbukan World Ninpo Bugei Federation, 2003.

U.S. Department of the Army. Soldier’s Manual of Common Tasks Warrior Skills Level 1. Washington, DC: Headquarters, Dept. of the Army, 2009.

U.S. Department of the Army. The Infantry Brigade. FM 7-30. Washington, DC: Headquarters, Dept. of the Army, 1995.

U.S. Department of the Army. Infantry Platoon and Squad. ATP 3-21.8. Washington, DC: Headquarters, Dept. of the Army, 2016. U.S. Department of the Army. Map Reading and Land Navigation. Field Manual 3-25.26. Washington, DC: Headquarters, Dept. of the Army, 2005.

[1] Shoto Tanemura, Ninpo Secrets: Philosophy, History and Techniques, 3rd Ed. (Matsubushi, Japan: Genbukan World Ninpo Bugei Federation, 2003), 228.

[2] Fujita Seiko, Ninjutsu Kara Spy-sen E (The Secrets of Koga-ryu Ninjutsu), Trans. Don Roley (Colorado Springs, Colorado: Freedom to Excel LLC, 2015), 36.

[3] Gingetsu Itoh, Gendaijin no Ninjutsu, trans. Eric Shahan (Charleston, SC: CreateSpace, 2014), 150-55.

[4] For descriptions of these features, see Chap. 10 of U.S. Department of the Army, Map Reading and Land Navigation, Field Manual 3-25.26 (Washington, DC: Headquarters, Dept. of the Army, 2005); as well as ArmyStudyGuide.com, “Identify Major / Minor Terrain Features,” https://www.armystudyguide.com/content/army_board_study_guide_topics/land_navigation_map_reading/identify-major-minor-terr.shtml (accessed August 31, 2021); and OEC G&V, “SMCT: Identify Terrain Features on a Military Map,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YZJaV1MARhc (accessed August 22, 2021); and .

[5] More recently, the order of considerations has changed slightly to make the acronym OAKOC (Obstacles, Avenues of Approach, Key Terrain, Observation and Fields of Fire, Cover and Concealment)

[6] The image is taken from Chapter 5 of U.S. Department of the Army, The Infantry Brigade, FM 7-30 (Washington, DC: Headquarters, Dept. of the Army, 1995).

[7] This image is taken from U.S. Department of the Army, Soldier’s Manual of Common Tasks Warrior Skills Level 1 (Washington, DC: Headquarters, Dept. of the Army, 2009), Figure 071-326-0502-1. Individual Movement Route, 3-168.