In the last article, we discussed some guidelines and principles of operating in urban terrain. In this article, as well as the one to follow it, we will specifically examine how to move stealthily in such an environment for the purposes of escape and evasion. In this article, we focus on stealth movement for outdoors in urban settings.

We began the last article with brief reference to okuton (屋遁, “house escape” or “building escape”), which is one of thirty methods for escape and evasion attributed to the feudal Japanese ninja and known as the tenchijin santon no hō (天地人三遁の法, “heaven, earth, man-three methods of escaping,” each of these three methods has ten sub-disciplines for a total of thirty). Here we consider how one early 20th-century author on the ninja, Itoh Gingetsu, described this art. For him, it is comprised of the use or successful negotiation of any buildings or manmade structures such as “fences, stone walls, hedges and so on […].”[1]

Obviously, these structures can be used to conceal oneself such as by hiding inside or behind a building, but Itoh focuses more on being able to efficiently negotiate the urban environment, à la parkour.

He points out how this requires mental flexibility and confidence as well as a high degree of physical fitness and agility. Itoh makes several similes with animals or nature in this regard:

“[…] be like a spider and stick to the walls, do as the rat does and cross roof beams and Nageshi. Slip underneath the floor as a weasel does or, if necessary, cross from rooftop to rooftop as a cat would do and fly off the kawara clay roof tiles as lightly as rain. Kick up the tatami mats in the main hall and shuffle in the confines like a mole. Other times you will need to break through a wall and leap over a fence. Anything can happen.”[2]

Note the emphasis at the end of this statement that one should be prepared for all possibilities, as well as the theme which runs throughout the quote to be flexible and adapt accordingly to such contingencies as they arise. These sentiments are reminiscent of another concept attributed to the ninja, the notion of banpen fugyō (万変不驚, “10,000 changes, no surprises”), which seems especially appropriate for the complex, fast-paced and rapidly changing nature of urban environments.

Following in the spirit of the method of okuton and seeking to recreate its essence for modern times for the purposes of escape and evasion for self-protection, this article has largely drawn from the US Army’s FM 90-10-1 An Infantryman’s Guide to Combat in Built-Up Areas as well as STP 21-1-SMCT Soldier’s Manual of Common Tasks Warrior Skills Level 1 in the sections entitled, “Perform Movement Techniques During an Urban Operation” and “Select Hasty Firing Positions During an Urban Operation,”as well as from other manuals that are specifically devoted to MOUT (Military Operations in Urban Terrain). Here, however, we have attempted to adapt these methods and approaches to civilian escape and evasion needs, whether armed or unarmed. Also consulted was literature on parkour, and we draw especially from The Ultimate Parkour & Freerunning Book by Witfeld, Gerling and Pach. Yet the reader is also referred to and encouraged to avail themselves of training in other disciplines that may also prove beneficial, such as climbing, bouldering and mountaineering as well as even the obscure literature on the little-known pastime of “night climbing” or “buildering.”

Proceeding now to the main content of this article, it consists of various commonly encountered situations and opportunities in urban terrain as well as potential approaches for dealing with these. We turn first to one of the most fundamental aspects of operating in urban terrain: corners and how to observe and move around them.

Observing around corners: Passing corners involves leaving dead space and potentially exposing oneself to an observer that one was hitherto concealed from. Thus, it is important to recognize corners ahead of time and not to expose oneself (such as by walking past corners unaware of them or by allowing one’s shadow or equipment to protrude beyond them) prior to making a visual reconnaissance of the area on the other side of the corner.

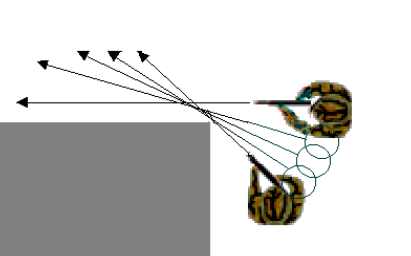

“Cutting the pie” or “pie-ing the corner,” as the cornerstone of building/room-clearing techniques, discussed at greater length in the next article, is probably the most secure way of observing around a corner. Ideally, one should be as far away from the corner being pie-ed as possible or at least as practical. This allows for greater standoff, should the enemy be immediately on the other side of the corner, as well as considerable responsiveness, since one is already standing upright on two feet, and can move relatively quickly, rather than when lying on the ground in a prone position, as advised by STP 21-1-SMCT and other manuals dealing with MOUT and found in the next technique.

This alternative to cutting the pie should only be used when the enemy is likely further away and not immediately on the other side of the corner. One lays flat on the ground, right next to the wall or other object, and very slowly peek one’s head around the corner, only as far as is necessary to observe.

The idea is that the head peeking around the corner, due to its appearing at a low height, is less likely to be recognized for what it is, if it is noticed at all, and may be misinterpreted as something else, like a shadow. Conversely, peeking around the corner at head-height will likely be immediately recognized as such. It is also more likely to draw immediate enemy small arms fire. Being close to the wall is intended to reduce exposure from other angles.

Observe around obstacles: While observing around corners was just discussed, it should be mentioned that when looking beyond obstacles in general, it is important to look around, under or through them rather than over. This is because looking over obstacles substantially increases one’s risk of exposure through silhouetting.

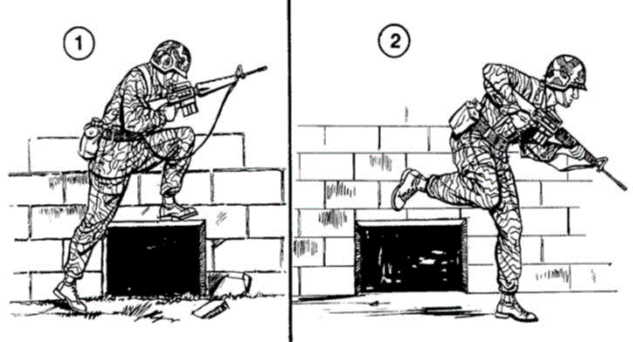

Moving past windows: To prevent silhouetting oneself through windows, it is best to move under them using a crouched walk, squatting walk or crawling.

Alternatively, if it is a basement window, it is preferred to step or jump over it rather than simply walking past it. Hence, do not make the mistake of exposing one’s head and upper body while passing a window or failing to notice a basement window and simply walking past it, thus exposing one’s legs.

Moving across open areas: Avoid staying in or crossing open areas whenever and wherever possible. Open areas are places that afford little or no cover and concealment. Examples include streets, squares, courtyards, parks, lawns, etc. It is preferrable to bypass open areas by contouring around them or boxing around them with four successive 90-degree turns (R-L-L-R or L-R-R-L). Sometimes, however, crossing an open area may be inevitable. When this is the case and you must cross an open area, be certain to do the following to mitigate your risk of exposure and being detected or engaged by an enemy:

-Visually reconnoiter the area to be crossed as well as one’s destination and next selected position prior to moving.

-Choose the most direct route possible. All variables being equal, the fastest route from point A to point B is a straight line.

-Whenever possible, select a route that can afford some positions of CCC.

-Dart between such positions of CCC with ideally no longer than 3- to 5-second rushes. This not only reduces exposure to visual detection, but it also makes one more difficult to target with firearms.

-After each sprint, pause briefly to look and listen for indications that you have been compromised as well as to visually reconnoiter the area and your next position before moving again. Watching mice scurrying in the open, running in short bursts interrupted by brief pauses, can be very instructive for how this ought to be performed.

Moving parallel to buildings/walls: Moving closely alongside walls substantially reduces one’s exposure. This is especially true if there are shadows within which one can remain and move. If properly moving past windows, as discussed above, for someone within the building which one is moving alongside to see oneself, they would have to physically stick their head out of a window.

Moving parallel to a building or wall also helps to reduce the area that one must constantly observe and scan to maintain security and situational awareness.

These points are among the important benefits ascribed to the sideways cross-step method of yoko aruki (横 歩, “sideways walk”) attributed to the feudal Japanese ninja. One can use this technique to travel quickly, quietly and closely to walls, including remaining within any shadows provided, while also being able to observe a 180-degree arc with a building or wall behind oneself.

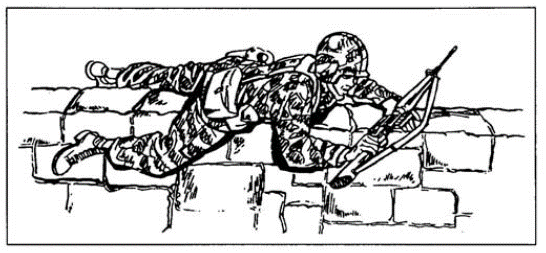

Crossing walls and other obstacles: Prior to crossing any wall or other obstacle, visually reconnoiter the other side to determine what is there, whether that be an adversary, a long drop or other hazards. If the decision is made to proceed, find a low place to cross, if available, and cross quickly over the top, pressed as closely as one can to the obstacle to maintain as low of a silhouette as possible. The quickness with which this is done helps to reduce one’s duration of exposure.[3]

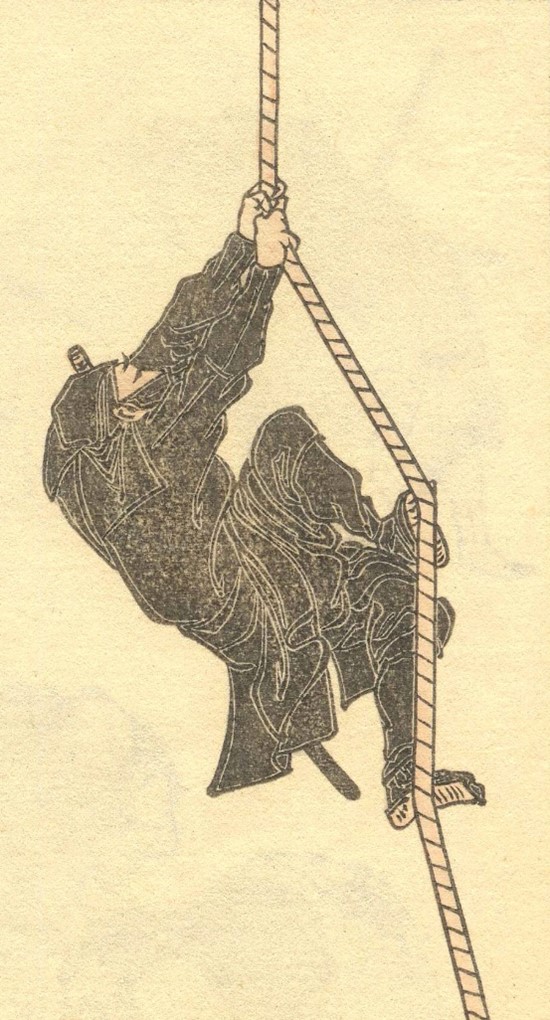

Climbing (ascending and descending): One may use external vegetation like trees and vines, structure-supporting poles, drainpipes or other structural features that could serve as hand- and foot-holds to ascend or descend from obstacles like walls or to reach or descend from windows or rooftops. Yet a substantial risk of severe injury or death remains with such methods.

A similarly risky and even life-threatening option is the use of ropes. Undamaged and well-made ropes, with sufficient tensile strength to safely support one’s weight, that are attached reliably to a secure anchor point that can also support one’s weight, such as with a grappling hook or by being tied off properly, can also be used for ascent or descent. Yet it should be noted that it is much easier to use ropes to descend rather than to ascend. The latter is extremely physically demanding and proves quite challenging to the average person.

Such abovementioned risks and challenges can be mitigated, though not entirely eliminated, through training, practice and conditioning in correct climbing technique as well as the use of proper climbing equipment. There is even a rare or emergent sub-branch of climbing for specific use in urban areas that is known as “urban climbing” or “buildering” (a combination of the terms “building” and “bouldering”).

We return to the issue of specialized climbing training below, but there are somewhat safer options available (though they are not entirely risk-free) and for the most part, they require less specialized equipment, training, practice and physical conditioning.

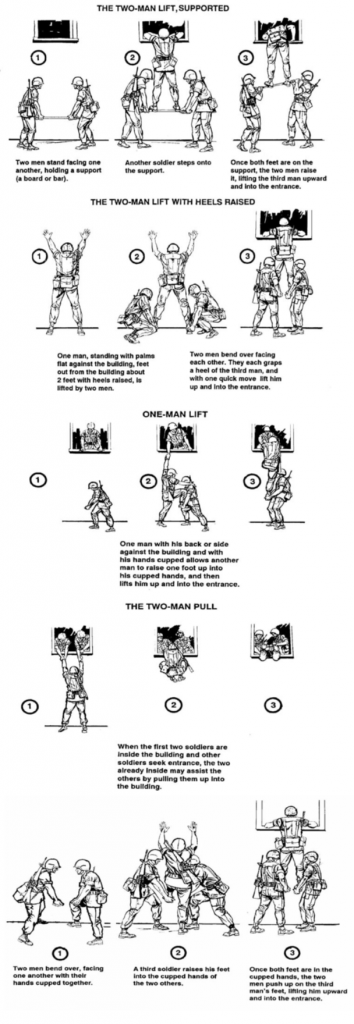

One might find existing ladders or stairs attached or adjacent to the structure that could be used, like a fire escape, or one may find ladders or make use of improvised ladders or makeshift “stairs,” such as utility boxes or vehicles that are immediately next to a structure and can thus be used as a kind of stepstool to reach a higher level.

Moreover, to overcome low heights, such as low walls, it may be possible to do so oneself, by running up the wall or other vertical surface using a technique known variously as shōten no jutsu or passe muraille, discussed below.

Yet partner assists can also be invaluable, whether with supplemental improvised equipment, like a wooden board or metal bar, or without them, relying on one’s partners’ bodies, such as using their clasped hands like a stirrup.

But returning to the issue of specialized skillsets, some obstacles are higher or more difficult to overcome than is allowed for by the abovementioned techniques. It is thus advisable to have basic knowledge and proficiency in climbing, and of course a sufficient level of physical conditioning to use it.

There is in fact a category of climbing developed in and particularly suited for urban environments known, inter alia, as “urban climbing,” “buildering,” “night climbing” or “roof climbing.” Interestingly, dating back as early as the late 19th century, a small body of literature on this topic emerged from students at the University of Cambridge who pursued this as a sort of clandestine pastime, which likely inspired a similar student movement at the University of Oxford.[4] Yet this is clearly part of a broader phenomenon and basic human exploratory impulse. Even the current author recalls such exploits not only at university on the rooftops of his dormitory, but also even throughout high school.

Yet such urban climbing is almost always unregulated, can be extremely dangerous and is usually illegal. Thus, the reader is strongly advised against undertaking such a pursuit. Alternatively though, foundational climbing skills, which could prove easily adaptable to urban structures in the case of a true emergency, can be acquired safely and legally at gyms or in courses for general rock climbing, bouldering, mountaineering, etc.

Moving across rooftops: Obviously, moving across rooftops is extremely dangerous and should be avoided if there is any way possible to do so. Not only is there a substantial risk of slipping and falling off of the roof, possibly leading to severe injury or death, but being caught on top of a roof can trap oneself, much like climbing up a tree or hiding in a cave with only one exit. The early twentieth-century author on the ninja, Itoh Gingetsu, referred to this type of situation with the expression: kikutsu ni iki nashi (鬼窟に生なし, “no escape from the devil’s lair [or demon’s cave]”).[5]

Yet some circumstances may require temporary use of a rooftop to facilitate escape. When this is the case, be certain to visually reconnoiter your next position and proceed carefully, to avoid slipping and falling, as well as to maintain a low silhouette, to avoid being detected visually. Crawling on all fours either face down or face up (like a crab walk), especially on a sloped roof, or squatting or crouched movement can help to not only reduce one’s silhouette to help prevent detection, but also to lower one’s center of gravity, to avoid falling. If an adversary may be inside the building on which one is moving, be certain to move softly, since the sound of movement on the roof will surely attract unwanted attention.

Use of Subterranean Routes: Urban areas may have underground/subterranean features that could help facilitate stealth for escape and evasion, such as subways, catacombs, basements, cellars, underground parking garages, bunkers, fallout shelters, sewers and weather drainage tunnels. But to be able to use these areas, one must first not only know that they exist but also be familiar with their design and how they could be used for concealment and reaching a safe place. The next article on movement indoors provides guidance that also applies to such subterranean settings, but here, we will focus on the dangers inherent in the latter two examples: sewers and weather drainage tunnels.

Sewers may seem like a useful option, yet there are some serious risks involved which probably outweigh any benefits. Sewers are highly dangerous hygienically as well as due to noxious and potentially lethal fumes. Thus, it is extremely inadvisable to ever attempt to traverse through these. In most developed countries, sewer systems are well blocked off and inaccessible anyways. Mines are also of course extremely dangerous.

Weather drainage tunnels are only slightly better than sewers, but in extreme situations, the latter might be one’s only choice. During the current author’s teen years, he spent much time exploring the weather drainage tunnels of his hometown, though he did so not knowing the serious risks involved and would strongly discourage anyone else from doing the same.

But by way of illustration of the potential usefulness of subterranean routes, as part of one of his many fairly innocent youthful misadventures, he made use of a weather drainage tunnel to elude a local police patrol (which was pursuing him and his best friend for the minor legal infraction of driving a four-wheeler on city streets and in the middle of the night). To escape, after parking their vehicle in a concealed location, they then instinctively employed a series of basic urban escape and evasion stealth maneuvers that ultimately culminated in crawling through around 100m of weather drainage pipe to successfully elude pursuit and reach a safe bed-down location despite active professional pursuit.

Some weather drainage tunnels can be traversed while standing and with a clear view of the exit on the other side. Others have a labyrinthine quality with multiple routes including small pipes where it is only possible to crawl through, if they are even large enough to traverse at all.

Be warned, however, that if it is raining, these can quickly fill with water, thus one risks drowning. If there is insufficient ventilation, toxic fumes can replace oxygen and cause death without one ever realizing that they are breathing such fumes. This is not to mention how if the infrastructure is old and dilapidated, a collapse is also possible, perhaps crushing or trapping oneself, and one may not have good enough mobile phone reception to call for help. Moreover, if you enter a weather drainage tunnel without knowing that there is a usable exit, then you encounter the same situation of being trapped without an escape route, as discussed above: kikutsu ni iki nashi (鬼窟に生なし, “no escape from the devil’s lair”).

In sum, one should never use sewers and the use of weather drainage tunnels is also strongly discouraged. Though knowing that such advice will not stop everyone from trying, it is underscored here that if it rains, one risks drowning; without proper ventilation, one risks death from noxious fumes and there are also the risks of being crushed during a collapse or being caught without an exit. So, very rarely if ever would the benefits of using weather drainage tunnels outweigh the drastic risks. Again, it is thus strongly discouraged here.

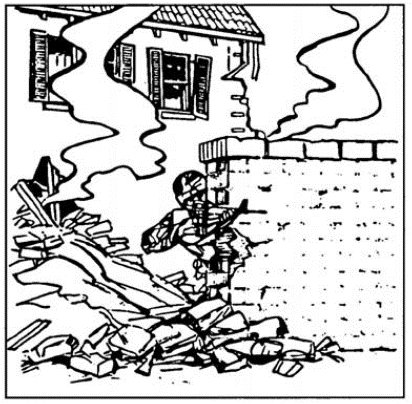

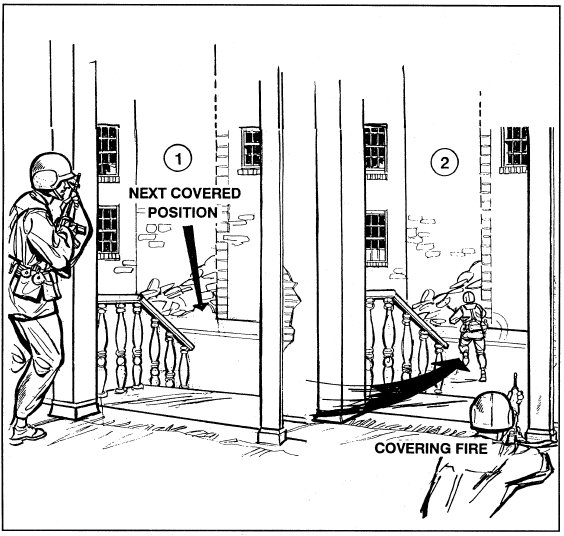

Use of External Doorways: Before proceeding specifically to indoor situations with the next article, an especially salient liminal or transitional situation must be mentioned, namely, external doorways. It must be noted that doorways are highly predictable avenues for entering or exiting buildings. Thus, using these should ideally be avoided or at least avoiding the use of main entrances. In practice, however, this may well be unavoidable. If so, it should then be undertaken with the utmost caution and with full awareness that an ambush could await one and the kill-zone may very well be the doorway itself. Therefore, visually reconnoiter and select one’s next position prior to passing through such a doorway, move quickly through the doorway to reduce exposure and, when in a group, have an ally positioned and ready to provide assistance should it prove necessary.

On the latter, in the below image, we see how US Army doctrine calls for having allies lay in wait to provide covering fire while passing through a doorway and toward the next covered/concealed position. If operating in a group, whether armed or unarmed, it might likewise be appropriate for companions to wait in reserve to provide support and assistance to their allies crossing through a doorway, in the event that there is an ambush on the other side.

Rapid Stealth Movement: Speed as Security

As already discussed at some length in the preceding article, sometimes it may be necessary to move swiftly to minimize exposure, to quickly establish distance from a pursuer or to expediently reach a safe place.

While the above method discussed for crossing obstacles maximizes silhouette reduction for passing over barriers like walls and fences, there are faster methods for situations in which speed must take priority over stealth, which is the main focus of the next paragraphs. There is also a much broader range of obstacle types to be considered beyond barriers like walls and fences, such as drops, elevated areas and gaps.

Military obstacle course training tends to use a more heuristic approach to learning, largely having participants discover their own ways of negotiating different types of obstacles. Participants typically receive a demonstration of someone else passing through such a course, but are then expected, without much detailed instruction on the finer points, to repeat it themselves. There are, however, other approaches that do not require “re-inventing the wheel” and which facilitate learning the most rapid and efficient means of overcoming obstacles, including the finer intricacies.

Of particular interest in this regard is the training discipline, sport, art and form of self-defense known as parkour (originally, les parcours). While its application is certainly not limited to use outdoors or even urban environments generally, it is especially suited to these and is typically practiced in such settings. It should be noted, however, that there is a distinction between parkour and the related and overlapping discipline of freerunning. Though they share the same foundation and the lines between the two are often blurred, the latter is more an athletic and artistic pursuit, while parkour is more specifically suited to escape and evasion.

Perhaps with roots in French military obstacle course training as well as the experiences in the Paris Fire Brigade of the father of the founder-figure, David Belle (b. 1973), parkour is surely an art form in and of itself, incredibly vast, complex and worthy of detailed study. In fact, it has become increasingly popular and institutionalized, even becoming the subject of serious academic study in the field of Exercise and Sports Science (ESS). It would thus be wise to benefit from the tremendous amount of physical and intellectual effort that have gone into developing and refining the most efficient methods for moving from one point to another in spite of obstacles in between. It is characterized by continuous forward movement.

Here, we regrettably highlight only a handful techniques, focusing on those which we feel are most relevant to escape and evasion. The techniques identified here seem the most appropriate for inclusion in a personal repertoire and training plan intended for escape and evasion. They draw from the impressive and detailed work The Ultimate Parkour & Freerunning Book by Witfeld, Gerling and Pach. There are also numerous other helpful resources, like The Parkour and Freerunning Handbook by Dan Edwardes.

There are of course also an ever-growing number of tutorials and demonstration videos available online, of varying levels of quality. Examples can usually be easily found, for instance, by searching for the French name for a particular technique or skill to be trained followed by the word “parkour.” But the foundational skills and techniques from Witfeld, Gerling and Pach that seemed most relevant to practice for civilian escape and evasion include, with a slightly simplified/modified arrangement to fit the present context:

Balancing (équilibre)

Running (courir)

Passe muraille (“wall pass”)

Tic-tac

Jumping (sauter)

Saut de précision (“precision jump”)

One-foot precision jump

Two-foot precision jump

Running precision jump

Saut de fond (“depth jump”)

Wall Dismount

Landing (reception)

Landing on feet

One-foot landing

Two-foot landing

Landing with hand assistance

Roulade (“roll”)

Saut de bras (“arm jump”)

Vaulting (passement)

Step Vault

Passement rapide (“speed vault”)

Lazy Vault

Demi-tour (“turn [vault]”)

Hanging, Swinging and Releasing (lâché and franchissement)

Again, however, this is just a list of some key basic techniques and skills that could prove especially useful for escape and evasion. It cannot convey the impressive efficiency and artistry with which skilled traceurs (practitioners of parkour) move through their environment from point A to point B smoothly and rapidly while negotiating obstacles in between.

Balance (équilibre): Balance is a basic ability that traceurs strive to gain mastery of. It should be practiced whether static or moving and whether on two feet or on all fours. Balance becomes especially crucial at elevated heights. An example might be walking or moving on all fours to cross an elevated beam or narrow ledge.

Running (courir): Running is one of the fundamental forms of human locomotion, a means of physical exercise, a basic stealth movement technique and of course a baseline activity for when one must use speed for escape and evasion. Running is also a basic technique of parkour which can not only be used to move quickly from point A to point B, but it can also be used to overcome obstacles that are within the reach of one’s stride, such as to ascend up a series of stepped surfaces much like if they were simply a staircase of large steps.[6]

There are two particular techniques that use running to overcome obstacles and which were prefigured in reports of the feudal Japanese ninja running up walls or other vertical or nearly vertical surfaces with a technique called shōten no jutsu (“climbing to the heavens,” 昇天の術), which also appears in the training of modern practitioners of the martial art called ninpō (忍法).[7] In parkour, techniques that make use of such running up of walls are referred to with the words passe muraille and tic-tac.

Passe muraille (“wall pass”) involves running toward and up a wall or similar surface to mount and cross that obstacle. Once one has reached the top, it may involve a planche (“plank”), that is with a grip on the top of the wall or other obstacle, “muscling up” on top of it.

Similarly, tic-tac is a technique in which one can gain height by running up to, stepping onto and pushing up and off to one side of a wall or similar surface, such as to facilitate leaping and clearing the top of an adjacent obstacle or grabbing the top of an adjacent wall to then planche up and climb over it.

Jumping (sauter):Prefiguring its importance in parkour, jumping or “flying” skills (hichōjutsu, 飛鳥術) were particularly emphasized as a fundamental ninja skill by Fujita Seiko (1898-1966), described widely as the last Koga ninja,[8] as well as by Itoh Gingetsu[9] and leaping is one of the foundational skills among contemporary practitioners of ninpō, with such techniques as happō tenchi tobi (八方天地飛び, “eight directions, heaven and earth leaping”).[10] Similarly, Fujita described six categories: jumping forwards, backwards, sideways and diagonally along with jumping for height as well as for specific distance, sounding very much like the saut de précision of parkour, which we now turn our attention toward.

Precision jumps can be one-footed, two-footed or performed while running. One-footed precision jumps allow one to cover the least amount of distance, while two-footed precision jumps allow more and running precision jumps allow for covering the greatest amount of distance, though the greater the distance, the more difficult it is to land precisely.

Sauts des fonds (“depth jumps”) consist basically of dropping from a higher level to a lower one. Practitioners of ninpō refer to this as tobi ori (“jumping down,” 飛び降り).[11] Witfeld, Gerling and Pach advise keeping one’s head up and eyes on the targeted landing site during flight to avoid leaning too far forward.[12] A related technique in ninpō is known as tobi komi (飛び込み, “diving”), in which one leaps by diving head and hands first.[13] This is analogous to the parkour technique known as saut de chat (“cat leap”).

The technique known as the “wall dismount” can be used when a drop is too high to simply drop down from while standing. Instead, one lowers oneself to either sit on or hang by the arms from the ledge, wall, etc., and then drop down to the lower level.

Landing (reception): Every jump or drop is followed by a landing. The aim of landing techniques is to safely absorb the force of impact to avoid injury and also to facilitate continued forward movement. Landings may be one-footed, two-footed, on all fours or involve rolling with the entire body.

While one-footed landings are generally, but not always, best suited to leaping at the same level, two-footed landings can be used for these as well as for when there is a substantial height difference between the take-off and landing locations.

One important one-footed landing technique involves landing in a lunge position, from which one can seamlessly transition to running forward. Two-footed landings can also be supplemented with the use of the hands to absorb impact and divert one’s movement.

An even further and more dramatic means of dissipating the force of impact and diverting or converting it into continued forward movement, especially after jumping a longer distance at high speed or dropping to a substantially lower level, is to somersault along the ground or roll (roulade), upon landing.[14]

This is similar to and based on the same principles as how paratroopers are taught to roll upon landing or how the abovementioned ninpō technique known as tobi ori is often completed with a technique known as zenpō kaiten (前方回転, “forward roll”) for this very same purpose.

Lastly, the saut de bras (“arm jump”) involves landing in a position where one is hanging by the arms from an edge, such as the top of a wall or a roof. From there, one can either drop down or muscle up to mount the structure.[15]

Vaulting (passement): Vaulting techniques are designed to overcome obstacles that are between hip and chest height, such as railings and small walls.[16] Like parkour generally, a key aspect of vaults is continuous forward movement beyond the vaulting movement itself. There is a plethora of diverse vaulting techniques, but we limit ourselves here to mentioning four selected vaults that seem the most relevant to escape and evasion while still being relatively feasible to master.

The “step vault” is a good foundational technique to begin with before proceeding to more advanced vaults. It is especially suitable for slower approaches.[17]

After the step vault has been mastered, the “speed vault” (passement rapide) is much easier to accomplish and it has the benefit that it can even be executed at a dead sprint.[18]

Another useful and relatively easily learned movement is the “lazy vault,” which is especially useful when approaching an obstacle from a diagonal angle.[19]

The last type of vault to be mentioned here is the demi-tour (“u-turn [vault],” “turn around [vault]” or simply “turn [vault]”). It involves leaping over an obstacle while supporting oneself with the hands on top of it, turning to face the direction from which one came while passing over the obstacle and then hanging before dropping to a lower level.[20] The practical benefit of this is that if one is leaping over an obstacle that has a drop on the other side, one can use this vault to reduce one’s elevation and momentum before the drop and even to pause and assess before deciding to actually drop.

Lâché and Franchissement

The term lâché (literally meaning to “let loose”) describes movements that involve hanging, swinging from and letting go of an overhead object such as a bar, beam or tree branch. The related body of techniques referred to with the term franchissement (“crossing”) also involve hanging, swinging and letting go, but they specifically entail doing so to pass over an obstacle or through an opening.

Conclusion

In this article, we have addressed a range of techniques, skills and considerations regarding the use of stealth for self-protection when outdoors in urban environments. We have drawn knowledge from works on military operations in urban terrain, but also from elsewhere, especially with regard to parkour, but also “buildering.” In the next article, we shift our attention to operating indoors in urban environments. In this endeavor, practices for “clearing” urban spaces take on a special significance.

Bibliography

Buckley, Andy. “Night Climbing in Cambridge.” InsectNation, 5 June 2007, http://insectnation.org/nightclimbing/nightclimbing.html.

Edwardes, Dan. The Parkour and Freerunning Handbook. London: Virgin Books, 2009.

Fujita, Seiko. The Secrets of Koga-ryu Ninjutsu: A Translation and Editing of Fujita Seiko’s “Ninjutsu kara Spy-sen e” by Don Roley. Trans. Don Roley. Palmer Lake, CO: Freedom to Excel LLC, 2015.

Fujita, Seiko. What is Ninjutsu?. Trans. Eric Shahan. Leipzig, Amazon Distribution GmbH, 2017.

Itoh, Gingetsu. Gendaijin no Ninjutsu. Trans. Eric Shahan. Charleston: CreateSpace, 2014.

Itoh, Gingetsu. Ninjutsu no Gokui. Trans. Eric Shahan. Charleston: CreateSpace, 2014.

Tanemura, Shoto. Ninpo Bugei, Volume 1: Fundamental Taijutsu, 7th Ed. Matsubushi, Japan: Genbukan World Ninpo Bugei Federation, 2007

Tanemura, Shoto. Ninpo Secrets: Philosophy, History and Techniques, 3rd Ed. Matsubushi, Japan: Genbukan World Ninpo Bugei Federation, 2003.

US Army, FM 3-06.11 (FM 90-10-1) Combined Arms Operations in Urban Terrain (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 2002).

US Army, FM 90-10-1 An Infantryman’s Guide to Combat in Built-Up Areas (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 1993).

US Army, STP 21-1-SMCT Soldier’s Manual of Common Tasks Warrior Skills Level 1 (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 2009). Witfeld, Jan, Ilona E. Gerling and Alexander Pach. The Ultimate Parkour & Freerunning Book: Discover Your Possibilities. Maidenhead, UK: Meyer & Meyer Sport, 2011.

[1] Gingetsu Itoh, Gendaijin no Ninjutsu, trans. Eric Shahan (Charleston: CreateSpace, 2014), 98.

[2] Ibid., 98.

[3] See 071-326-0541 “Perform Movement Techniques During an Urban Operation,” in US Army, STP 21-1-SMCT Soldier’s Manual of Common Tasks Warrior Skills Level 1 (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 2009).

[4] Buckley, Andy. “Night Climbing in Cambridge.” Insectnation, 5 June 2007, http://insectnation.org/nightclimbing/nightclimbing.html.

[5] Gingetsu Itoh, Gendaijin no Ninjutsu, trans. Eric Shahan (Charleston: CreateSpace, 2014), 151.

[6] Jan Witfeld, Ilona E. Gerling and Alexander Pach, The Ultimate Parkour & Freerunning Book: Discover Your Possibilities (Maidenhead, UK: Meyer & Meyer Sport, 2011), 94-96.

[7] Itoh, Gendaijin No Ninjutsu; Shoto Tanemura, Ninpo Bugei, Volume 1: Fundamental Taijutsu, 7th Ed. (Matsubushi, Japan: Genbukan World Ninpo Bugei Federation, 2007), 33; Shoto Tanemura, Ninpo Secrets: Philosophy, History and Techniques, 3rd Ed. (Matsubushi, Japan: Genbukan World Ninpo Bugei Federation, 2003), 86.

[8] Seiko Fujita, What is Ninjutsu?, trans. Eric Shahan (Leipzig: Amazon Distribution GmbH, 2017), 42-44; Seiko Fujita, The Secrets of Koga-ryu Ninjutsu: A Translation and Editing of Fujita Seiko’s “Ninjutsu kara Spy-sen e” by Don Roley, trans. Don Roley (Palmer Lake, CO: Freedom to Excel LLC, 2015), 134-35.

[9] In particular, Itoh speaks of hikō jizai no jutsu (飛行自在の術, “the art of flying freely”), see his Gendaijin No Ninjutsu, 103-07.

[10] Tanemura, Ninpo Secrets, 85-86; Tanemura, Fundamental Taijutsu, 32.

[11] Ibid., 33.

[12] Witfeld, Gerling and Pach, The Ultimate Parkour & Freerunning Book, 112.

[13] Tanemura, Fundamental Taijutsu, 33.

[14] Witfeld, Gerling and Pach, The Ultimate Parkour & Freerunning Book, 126-30.

[15] Ibid., 186-91.

[16] Ibid., 130.

[17] Ibid., 132-34.

[18] Ibid., 134-39.

[19] Ibid., 140-43.

[20] Ibid., 166-72.